:: Encore Theatre Magazine ::

:: British Theatre: Polemics & Positions ::| [::..navigation..::] |

|---|

| :: Encore Front Page |

| :: Encore Revivals |

| :: Encore Futures |

| :: Encore Snapshots |

| :: Encore Polemics |

| :: Encore Resources |

| :: Encore Criticwatch |

| :: Encore Commentary |

| :: Encore on Encore |

| :: Encore Awards 2003 |

Encore Theatre Magazine

::Encore Heroes::Robert Holman [>]Encore Heroes # 1:

Mark Rylance [>]

Bill Nighy [>]

Ruthie Henshall [>]

Robert Holman

Why doesn't Robert Holman receive the acclaim he deserves? His playwriting is subtle, emotionally rich, morally complex, constantly beautiful, always imaginative. The anatomisation of our fear of the unknown, in Other Worlds, moments of inexpressible tragedy, bravery and desperation in The Overgrown Path and Across Oka. Bad Weather's gradual unfolding was one of the highlights of the RSC's last five years. Rafts and Dreams is one of the great post-war British plays, full stop.

His plays have inspired other playwrights, David Eldridge for one. Holman once described his writing method. 'I just write,' he said, 'until one of my characters says something or does something that surprises me.' Anyone who knows his plays will understand this; he creates a mood of provisional calm, groping sympathies between his characters, a truce of the heart which is then shatteringly broken by an event of appalling, bewildering horror: the eggs in Across Oka, the ape in Other Worlds, the storm in The Overgrown Flood, that flood in Rafts and Dreams.His tragedy, of course, is to have been born out of his time. The 1980s was not an era in which playwrights got taken that seriously, and he joins a list of forgotten figures in the era before Kane. He also wrote elliptically, his tones being quiet, muted, gentle. This was a time when brashness dominated theatrical statement, for good (Serious Money) and ill (A Map of the World). And now, when only urban twentysomethings are deemed worthy of theatrical treatment, we should remember that no one writes better for the very old and the very young, and that his writing has the quality of landscape; not simply that he writes about the country, sets his plays in it, draws characters from it, but the work itself bakes under fierce suns, is ever alert to the changing seasons, the filling of a sky with cloud; Holman's work undulates, the rhythms and tones rising and falling like a gentle measure of hills. His work is superficially realistic, but contains fathoms of metaphorical richness. He is hard to talk about; he provides very few 'issues'. His plays are not immediately graspable; they are as subtle and complex as our friends.

There is a new play, Holes in the Skin opening at Chichester this summer but his work aches for revival. The Oxford Stage Company's staid account of Making Noise Quietly in 1999 was the nearest major revival. The National should look at this work; he deserves a season, a systematic programme of revival (and republishing). He is a jewel.

Selected Plays

- 1974 Mud (Royal Court)

- 1977 German Skerries (Bush)

- 1980 Chance of a Lifetime (BBC, 'Play for Today')

- 1983 Other Worlds (Royal Court)

- 1984 Today (RSC: The Other Place)

- 1985 The Overgrown Path (Royal Court)

- 1986 Making Noise Quietly (Bush)

- 1988 Across Oka (RSC: The Other Place)

- 1990 Rafts and Dreams (Royal Court: Theatre Upstairs)

- 1992 The Amish Landscape (novel)

- 1998 Bad Weather (RSC: The Other Place)

- 2003 Holes in the Skin (Chichester Festival Theatre: Minerva)

:: Theatre Worker 1:18 PM [^] ::

...

Encore Heroes # 2::: Wednesday, June 11, 2003 ::

Mark RylanceAdmit it, didn’t the project to reconstruct Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre sound like a truly rotten idea? Soggy with misplaced ideas of authenticity, at times stodgily antiquarian, teetering on the quaint. It seemed obvious that its theatrical value would be negligible, that it would very soon dwindle into a third-rate tourist trap, with lesser and lesser actors traipsing through village-hall repetitions of the Bard-u-like favourites.

And then they appointed Mark Rylance as its artistic director. Under his guidance, the building has become an engine room for the production of a new attitude to Shakespearean performance. Rather than investigating Shakespeare in hushed laboratory conditions, the Globe’s a pretty raucous place, whose dynamics have required actors to relearn the rhythms and forces of their craft. They haven’t always succeeded, but it has been a valuable lesson that GCSE-clarity and pious textual fidelity has often been the cause (as in Barry Kyle’s King Lear two years ago). It seems as though the very spatial arrangements, the timbers and boards themselves have given the Globe, in the best sense, a pantomime atmosphere. This does not imply that the work done here is not serious; it should encourage us to expand what we mean by ‘serious’.

And Mark Rylance has so much of this to his credit. Last year’s experiment with all-male casts earned him some tutting, but was at least artistically vindicated by his own fluttering Olivia, gliding through Twelfth Night with Beijing Opera formality, but all the more to offset the poignancy of her misjudged attempts at romance. Politically, the decision is vindicated by this year’s upcoming Richard III and Taming of the Shrew, which will be played by all-female casts. The plays form part of the Season of Regime Change, a cheeky little title that adds another piece to the South Bank’s oppositional jigsaw, stretching from Ken Livingstone in City Hall, through the magnificent conceptual bullshitters at Tate Modern, past the new National, and on into the gradually revamping South Bank Centre.

The Globe has recovered little-known work by Shakespeare's contemporaries, houses an energetic playreading programme, and takes few soft options with its programming in the main space. What may once have seemed a curiosity - something between Disneyworld and the Sealed Knot - now seems theatrically inviting. Rylance dabbles in mysticism, once famously limiting his tour of Macbeth to performance spaces on ley lines, and his range of reference - I mean, visibly, on stage - suggests a mind whirling with invention, forming connections across the centuries, drawing an alternative map of British acting whose ley lines reach out well beyond the usual histories, to popular traditions, drawing on deep political commitments, and gesturing out to the worlds of the imagination.And Rylance as an actor continues to grow. He once said of his work at the Globe, with a candour and generosity that remains rare in British theatre, ‘I may not have always given such good performances, but I’ve always learned. I feel connected to a community of other actors and an audience, and that is something no other theatre could have given me’. It is this sense of performance and community that makes him so fascinating to watch; his endless inventiveness, the flexibility and range of his voice, his child-like love of experiment and novelty, these things have contributed to the vitality of his work at the Globe. But at the heart of that new-old building is one of the great actors of our age, powering the place like an old connection, sparking with dangerous energy.

Selected Stage Performances

1983 Peter Pan (Peter) Royal Shakespeare Company

1988 Hamlet (Hamlet) Royal Shakespeare Company

1989 Romeo and Juliet (Romeo) Royal Shakespeare Company

1993 Much Ado About Nothing (Benedick) Queen's Theatre

1994 True West (Lee/Austin) Donmar Warehouse

1995 Macbeth (Macbeth, also directed) Phoebus Cart (touring production)

1997 Henry V (Henry) Shakespeare's Globe

1998 The Merchant of Venice (Bassanio) Shakespeare's Globe

1999 Antony and Cleopatra (Cleopatra) Shakespeare's Globe

2000 Hamlet (Hamlet) Shakespeare's Globe

2000 Life x 3 (Henry) National Theatre: Lyttleton

2001 Cymbeline (Cloten, Posthumus, Physician) Shakespeare's Globe

2002 Twelfth Night (Olivia) Shakespeare's Globe

2003 Richard II (Richard) Shakespeare's Globe

Links

- Rylance's recent Guardian article discussing the announced all-women production

- Shakespeare's Globe Research Database, an academic website drawing together research on Shakespeare's Globe, old and new.

- Mark Around, a truly devoted fan site.

:: Theatre Worker 10:50 AM [^] ::

...

Encore Heroes # 3::: Sunday, August 10, 2003 ::

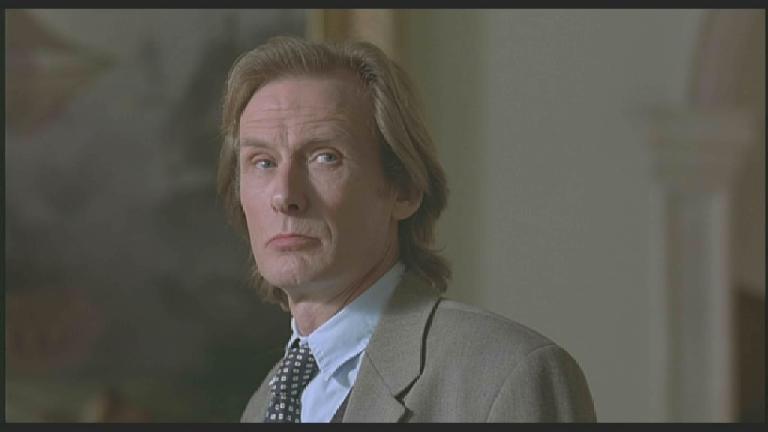

Bill Nighy

Watching Paul Abbott's terrific new political drama for the BBC, State of Play, Encore was once again struck by the joys of Bill Nighy, whose broadsheet newspaper editor, Cameron Foster, is another in a long line of journalists that he has brought to the screen and stage. This one is by turns brutal in his sarcasm with an idiotic staffer, simmeringly laconic with the police, bruised and touchy when his journalist son cockily swaggers his way onto the team. Quite apart from the excitement of the narrative, Nighy's performance is constantly rich, hilarious, broodily magnificent.

Born in 1949, he's now in his fifties and although he has been acting since the seventies, he's moved into the front rank in the last fifteen years. In a recent interview he half-jokingly remarked that he's been getting good parts ever since he lost his looks, and while this is too modest, his dashing features, that mane of Heseltine hair have nicely settled into a craggy old age. He manages to look world-weary and prowling, seedy and rakish. When he took over the part of Tom Sergeant in David Hare's Skylight from Michael Gambon, he replaced Gambon's massive delicacy with a vulpine energy, prowling around that room in an expensive coat, looking for corners to scent, charming and spitting and seductive and cruel.

I had the interesting experience of seeing him in Joe Penhall's Blue/Orange twice, about six weeks apart. Nighy plays an eminent, if eccentric, psychiatrist who seizes on the delusions of a young black patient to develop a theory of 'black psychosis', railroading a junior doctor, thus precipitating the clash that provided the climax of the play. Nighy was extraordinary: fizzing with intelligence, witty and spiteful and arch, playing the institution against itself. But after the first performance I wondered if that louche style - softening the consonants, foreshortening his sentences as he rushed from thought to thought, lurching territorially across his stage - was a little, well, selfish. Hugely entertaining, yes, but did it depend on a kind of chaotic adrenalin, unbalancing the ensemble, forcing the others (Andrew Lincoln and Chiwetel Ejiofor) to play catch-up? And then I saw it again and discovered that it was pretty much identical; each foreclosed word, each stray gesture, the sudden spitting emphasis on a word, it was all there.And I should have known. Nighy is not an actor for the indulgences of interiority, he's strictly outside-in. The ideas are conceived on the body, not pushed out from the depths, which has given him the steely control to be taken up by television, and performances in Dreams of Leaving (1980), The Men's Room (1991), Absolute Hell (1991), and The Maitlands (1993) linger in the memory. He has made less of an impact in film, though he's a wildly funny rockstar acid casualty in Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais's likeable Still Crazy (1998, left), in which he also sings the songs in an impressive stab at seventies hard-rock blues style ("All over the world tonight / Feet are hitting the ground ..."). Given the embarrassing hash most actors make of playing rock singers, Nighy, who sprinkles his interviews with reference to rock, country and blues, brought a real love and authenticity to the role.

But the theatre still seems to be his home; he's worked so much in new writing, which is usually led by the words, that we forget the force of his physical presence, the long distinguished nose, the cruel probing eyes, the careworn face, the reluctant, dangerous smile, and his roaming, territorial quality that seems to require a real space to occupy, to claim and make his own. Although there have been distinguished performances in several places, from the impact he made at the Liverpool Everyman in the mid seventies, through the rambling, visionary science-fiction experiment, The Warp, at the ICA, to Betrayal at the Almeida, his best work has been at the National Theatre, notably in Map of the World, Pravda, King Lear, Mean Tears, Arcadia, The Seagull (pictured, above), and Blue/Orange, whose in-the-round staging seemed to accentuate his restless exploring of space.

Perhaps Nighy would not suit classical roles, certainly he seems not greatly attracted to them; there's something so deeply contemporary about him, that in classics he would seem marooned from the energies and questions of our age that fuel his restless intelligence. As Trigorin in The Seagull he and Judi Dench's Arkadina did not gel, and some brief friskiness on a rug failed to convince us that they occupied the same world, let alone had fallen in love. Nighy brings a gift of immense wit and theatrical ease, casing the stage with ferocity and style. He's a buck, a wolf, a hyena, and he brings a savage magnificence into our theatre.Selected Performances

1979 The Warp ICA

1980 Dreams of Leaving (William) BBC TV

1983 Map of the World (Stephen Andrews) National Theatre: Lyttleton

1985 Pravda (Eaton Sylvestor) National Theatre: Olivier

1986 King Lear (Edgar) National Theatre: Olivier

1987 Mean Tears (Julian) National Theatre: Cottesloe

1991 The Men's Room (Mark) BBC

1993 Arcadia (Bernard Nightingale) National Theatre: Lyttleton

1993 The Maitlands BBC TV 'Performance'

1994 The Seagull (Trigorin) National Theatre: Olivier

1995 Skylight (Tom Sergeant) Vaudeville Theatre

1998 Still Crazy (Ray Simms) Film

2000 Blue/Orange (Robert) National Theatre: Cottesloe

2003 State of Play (Cameron Foster) BBC TV

Links

- You can listen to a RealAudio clip of Bill Nighy in Blue/Orange here

- You can also hear Bill Nighy singing from Still Crazy by clicking here and looking for the clip from 'All over the world'.

- There's an Independent interview from April 2001 here.

:: Theatre Worker Wednesday, June 11, 2003 [+] ::

...

Encore Heroes # 4:

Ruthie HenshallIn the hit musical Chicago, the ruthless showbiz lawyer confronts his client who believes her own recent publicity: ‘you're a phoney celebrity, kid,' he says, ‘In a couple of weeks no one's gonna know who you are.' Chicago, like Kander and Ebb's other great work, Cabaret, is a show with no illusions that entertainment is somehow beyond politics, ethics, value and art. Encore doesn't talk too much about musicals, but after a week that has seen the start of new television runs for Fame Academy and Pop Idol, we want to make some distinctions. And in Ruthie Henshall, we believe, you see something of the vital importance of entertainment.

Ruthie Henshall is probably the greatest musical performer in Britain. After apprenticeships in Cats and a touring production of A Chorus Line, she was part of the original cast of Miss Saigon and had a stint as Fantine in Les Misérables. She stood out as Polly in Crazy for You [pictured, below], but came to real prominence with her definitive performance of Amalia Balash in She Loves Me [pictured]. Taking on the part created by Barbara Cook was a tough move, but she claimed the part as her own, giving it a gawky vulnerability, a certain smart-talking feistiness, and a rare sense of genuine romantic sunshine. There's a gorgeous scene where she is visited in bed by the man who she doesn't realise she loves (don't ask); Henshall took us through frenzied, absurdist ungainliness (‘Where's My Shoe'), through a tearing row, to the comic delight of a new-old love dawning (‘Ice Cream'). Peggy Sue Got Married, much underrated, was built around her and she had a long and successful period on Broadway. She was the first Roxie Hart in London's current revival of Chicago [pictured], and she is currently the same production's Velma Kelly. Roxie showed she could do raunchy, and she gives Velma Kelly's sassiness an appealing neediness and comic vigour.To perform in a musical requires so much. You need to be able to be funny, to be moving, to act with sincerity and wink at the audience. You need a personality that fills Drury Lane, and of course you gotta sing, gotta dance. Obviously, this is why so many people are attracted to it. Equally obviously, it's why so few people can do it. But the illusion that people can do it is hollowing out the joys of the musical, and undermining the subversiveness of its pleasures.

Because there's a real continuity between the performance styles of the megamusical, of the cruise-ship sensibility of our boy and girl bands, and of talent-show TV. Stephen Gately of Boyzone has recently taken the lead in Joseph and His Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat; Jon Lee of S Club is about to take on the role of Marius in Les Misérables. Yesterday, The Independent reported a massive leap in the numbers attending Stagecoach's stage schools and workshops. The age group is the same as that targeted by the big record companies with S Club Juniors, Gareth Gates, and all the rest of them.

The key is in the titles: Fame Academy, Pop Idol. These children are being schooled to be famous, to be idolised, and they work backwards from there. The styles cannot be original and of course they're not meant to be. As Theodor Adorno wrote, 'Talented performers belong to the system long before it displays them'. It's not Simon Cowell who makes singers into bland chart- fodder. They do it themselves, in their bedrooms, hairbrushes in their hands and Celine Dion on the radio.And that's what is so wrong with this work. You don't need to be Stanislavky to demand some kind of understanding, some level of personal commitment and imaginative engagement with your performance. What we see in the Pop Idol auditions is a kind of professionalised emotion; the Mariah Carey warble, Celine Dion top notes; wasn't that crack last heard in Ronan Keating's voice? Didn't I see that inner turmoil flitting across Will Young's face? It's all demonstration of emotion with no understanding or commitment to that emotion. It's music for our numbed, consumerist age, not simply because it is bought by consumers, but because, in a profound way, it is produced by consumers. Shaped by market research yes, but internally, the minds and bodies of those performers are stuffed with the impressions of what they have seen and bought before.

And this is where the musical is so important, and why Ruthie Henshall is so worthy of admiration. No other theatrical form puts the bonds between audience and performer so centrally. In a privatised, individualistic world, the musical is the theatre form that above all else demands that the performers reach out to the audience. The audience's engagement is through its pleasure at the work of others; we delight in the performers' craft. In no other theatre form is craft so nakedly, so undisguisedly on display. The profoundest satisfactions in the musical - the best nights out - derive from the richest and most complex craft. When we watch Pop Idol, we are invited to scorn the hopes of others, and laugh at their failings. At a great musical we take pleasure from the connections made between people, and we show respect for other people's work. Ruthie Henshall's work demands respect, it devours us with pleasure, she delights, thrills, amuses, dazzles and does so with seriousness, intelligence, sensitivity, and huge depths of emotional power.

This is no small thing. The musical's always being held up as the most conservative theatrical form we have. But in the performances of Ruthie Henshall we see something important and quite counter to the values of our society.Selected Performances

1989 Miss Saigon (Bar Girl, later Ellen)Theatre Royal Drury Lane

1991 Children of Eden (Aphra) Prince Edward Theatre

1992 Les Misérables (Fantine) Palace Theatre

1993 Crazy for You (Polly Baker) Prince Edward Theatre

1994 She Loves Me (Amalia Balash) Savoy Theatre

1996 Oliver! (Nancy) Palladium

1997 Chicago (Roxie Hart) Adelphi Theatre

1999 Chicago (Velma Kelly) Shubert Theatre, NYC (London, 2003)

1998 Putting it Together (The Younger Woman) Ethel Barrymore Theatre, NYC

2001 Peggy Sue Got Married (Peggy Sue) Shaftesbury Theatre

Links:: Theatre Worker Sunday, August 10, 2003 [+] ::

- Ruthie Henshall has her own official website here.

- She has several fan sites on the web. This one is fairly sane, this one slightly less so.

...