|

|

Encore Theatre Magazine

::Encore Awards 2003::

Not voted for, no actual prizes awarded, arrived at by discussion among the members of Encore's anonymocracy, the Encore awards are designed to intervene, not to commemorate. We have no teams of reviewers, no corrective sampling, and obviously the ten or so figures involved in this survey have seen but a fraction of the year's work in the theatre. These are just the humble opinions of a group of regular theatregoers and theatre workers with very very good taste.

Best Front of House [>]

Best Translation [>]

Best Thing to Happen [>]

Best Artistic Director [>]

Best Lighting [>]

Best Design [>]

Best New Play [>]

Best Revival [>]

Best Front of House

Virtually nowhere in London has a front of house you look forward to going to. The Royal Court bar and restaurant (left) is lovely but not if there's a show going up when it's all bottlenecks by the stairs and scrums at the bar. The Barbican continues to feel as cosy as an aircraft hanger; the seats appear to have been arranged by some crazy misanthrope, the high concrete ceilings and tatty shiny floors crushing any conversation out of you.  A few theatre managements have contrived to defy the architectural horrors they were bequeathed: the success of the Lyric Hammersmith is to do with Neil Bartlett's wonderful programming, which manages to attract a huge and diverse audience to each production; it's certainly not the ambience of its first floor foyer, a misguided exercise in burolandschaft. With luck the redevelopment will allow the architecture to reach the standard of the audience and the policy. The National has introduced some well-placed lighting installations to liven up the general brutality; again, as with the Lyric, it's the buzz of the audience that has really transformed the feel of the building. The Battersea Arts Centre has a good cafe but the building as a whole hasn't been able to throw off its aura of municipal sternness. The new Hampstead theatre is an improvement on the last but it's felt rather a drafty place whenever Encore's been there; a space that cavernous really needs a throng. A few theatre managements have contrived to defy the architectural horrors they were bequeathed: the success of the Lyric Hammersmith is to do with Neil Bartlett's wonderful programming, which manages to attract a huge and diverse audience to each production; it's certainly not the ambience of its first floor foyer, a misguided exercise in burolandschaft. With luck the redevelopment will allow the architecture to reach the standard of the audience and the policy. The National has introduced some well-placed lighting installations to liven up the general brutality; again, as with the Lyric, it's the buzz of the audience that has really transformed the feel of the building. The Battersea Arts Centre has a good cafe but the building as a whole hasn't been able to throw off its aura of municipal sternness. The new Hampstead theatre is an improvement on the last but it's felt rather a drafty place whenever Encore's been there; a space that cavernous really needs a throng.

Most West End theatres are cramped, grubby, and full of faded tat. Anyone stupid enough to want to see We Will Rock You must do so in a building that looks like the Prozorovs' house in the National's Three Sisters, nicotine-stained, peeling, faded, just plain dangerous-looking. The Victoria Palace theatre is cleaner but comically cramped. And this is the theatre that introduced £55 tickets at the weekend for Tonight's the Night (and, mysteriously, £8 for a souvenir programme, when surely most visitors would pay double that to have the show scrubbed from their memories).The conditions in which you have to see these shows, I suppose, count as a righteous penance for the stupidity involved in your choice of evening's entertainment. Perhaps the aim is to depress the spirits so much that even the dismal flickerings of life on stage seem like a riot of joy and colour.

So, there's not much the celebrate in London. There are good examples of theatres that genuinely seem to reach out to their communities around the country - the West Yorkshire Playhouse is a good example. But some of the theatres most celebrated for their accessibility and inclusiveness are complacent about their audience's comfort: The Citz is a good example - the foyer's a mess, the beer is fantastically expensive, and they're going to ban smoking. No one has ever called the Tramway inclusive, but why don't they do something about that amenity-free wind tunnel of a foyer? So, there's not much the celebrate in London. There are good examples of theatres that genuinely seem to reach out to their communities around the country - the West Yorkshire Playhouse is a good example. But some of the theatres most celebrated for their accessibility and inclusiveness are complacent about their audience's comfort: The Citz is a good example - the foyer's a mess, the beer is fantastically expensive, and they're going to ban smoking. No one has ever called the Tramway inclusive, but why don't they do something about that amenity-free wind tunnel of a foyer?

The best front of house is not new; it's the same great bar that it ever was - it's the Traverse (right), particularly during the Festival, where it still becomes the place to meet people, chat about the work, and drink and smoke into the night.

Best Translation

There was some superb translation work this year. The flamboyance of an earlier generation of translators (the pyrotechnics of Ranjit Bolt, say) have yielded to a gentler, more probing approach. Nicholas Wright's work on the National's Three Sisters (from the indefatigable Helen Rappaport's literal version) was unflashy, quietly mature and graceful. Tanya Ronder's work on Peribanez wrought a contemporary theatre text from Lope de Vega's original without distracting modernisms, finding plainness and passion in its delicate storytelling.

One of the very finest pieces of work was David Greig's verison of Camus's Caligula, which respected the intellectual sinews of the play, but also brought out the visceral and harrowing theatrical journey of its anti-hero in a series of sharp, often comic, and poetically-inflected encounters.

There were some low points. There was no excuse for Peter Stein to base his version of The Seagull on Constance Garnett's ancient translation. And what was Martin Sherman thinking in his hideous translation of Pirandello's Cosi' e' (se vi pare), usually rendered Right You Are (If You Think So) which is hardly mellifluous, but is hardly improved by Sherman's title Absolutely! (perhaps) which looks and sounds risibly clumsy. The translation itself was no better - he'd just about got it out of the Italian, but hadn't entirely managed to get it into English. Here's something from the opening minute of the play: Amalia. Don't be absurd. We simply want justice. One doesn't leave two ladies standing in front of a door as if they were...

Dina. Hitching posts.

Can you imagine anyone saying such a thing? The spindly abstraction of 'one' and 'they' and 'a door'; and 'hitching posts', stuffing up your mouth with consonants and dropping limply on the brain (what's a hitching post again?). Simon Nye's Accidental Death of an Anarchist was spatchcocked by Fo's vice-like grip on his translators, offering opportunities for actors, but verbally running on empty.

The best translation this year, though, was Pam Gems's gorgeous rendering of Ibsen's The Lady from the Sea (Left). Somehow she managed to keep the individual lines clear and fresh, while leaving the whole as mysterious as the sea's depths.  So many moments stand out, but Encore particularly admired the conversation between Lyngstrand and Bolette on the duties of a wife. So many moments stand out, but Encore particularly admired the conversation between Lyngstrand and Bolette on the duties of a wife.

Lyngstrand. Miss Wangel - have you ever - I mean, did it ever occur to you - have you ever thought about marriage?

Bolette. I beg your pardon?

Lyngstrand. I have.

Bolette. Oh?

Lyngstrand. Yes. I think about it a lot. A woman could be transformed -

Bolette. Transformed?

Lyngstrand. - by her husband's influence.

Bolette. Why would she want that?

Lyngstrand. In order to ... so that she ...

Bolette Could share his interests, you mean?

Lyngstrand. Exactly.

Bolette. And acquire his abilities.

Lyngstrand. Absolutely. It could happen. Gradually. In a happy marriage.

Bolette. What about the other way round?

It doesn't look much on the page, but look closer. Every line is weighted effortlessly, it's instantly speakable which propels the conversation on, and it's that momentum that Bolette needs to derail her would-be suitor so deftly. The nascent feminism of the scene is clear, without being laboriously hauled up to the footlights. She's caught Ibsen's characters with tiny details: the punctuation of the exchange is superb. Don't laugh, these things matter, just look at it: the three false starts starts to Lyngstrand's opening gambit; the revealing certainty of those full stops in 'Yes. I think about it a lot.'; the sense of uncertain revision that courses through 'Absolutely. It could happen. Gradually. In a happy marriage'.

This is work that makes the original curl off the stage like smoke and it is Encore's translation of the year.

Best thing to happen

It would be boring to give this one to Nick Hytner too, so we won't. There are plenty of contenders for the worst thing to happen; £55 weekend tickets for the vile Tonight's the Night; the vile Tonight's the Night itself; The New Statesman's decision to stop theatre reviews because people 'don't write political plays any more' (and then changing their minds and hiring, wait for it, Michael Portillo as their reviewer); then there was the limping start to Hampstead Theatre's first season after reopening, the squalid farce of the RSC's plans for Stratford, the continuing creative decline of the Royal Court. I'm sure you can add your own suggestions.

Lots of the best things to happen were revivals, plays and new artistic directorships, but these we've already covered. The best thing to happen must be the announcement of plans for a Scottish National Theatre. Encore acclaimed this shortly after its announcement and the plans for a dispersed, roaming, theatre is located in the imagination as much as it is in geography seems undeniably the model of a National theatre for the Twenty-First Century.

Of course, the ambition and vision of the project is already clouding. The arms' length relationship between the Scottish Arts Council and the Scottish Executive is slowly but surely becoming a bear hug.  The blame for this lies can be largely laid at the feet of James Boyle (right), who is proving about as popular at the SAC as he was at Radio 4, and is now cosying up with the Scottish Executive and the macho West Coasters in Holyrood, Frank McAveety (arts minister who loves football more than art) and Jack McConnell (never yet seen at the theatre). This trio have decided that the new priorities are: 'audience-focused' work (meaning populism), and 'children and young people' (meaning educational work that can go into schools without ruffling any feathers). The blame for this lies can be largely laid at the feet of James Boyle (right), who is proving about as popular at the SAC as he was at Radio 4, and is now cosying up with the Scottish Executive and the macho West Coasters in Holyrood, Frank McAveety (arts minister who loves football more than art) and Jack McConnell (never yet seen at the theatre). This trio have decided that the new priorities are: 'audience-focused' work (meaning populism), and 'children and young people' (meaning educational work that can go into schools without ruffling any feathers).

In other words, as they've said quite explicitly, 'your priorities are no longer our priorities'; displaying a jaw-droppingly contemptuous mistrust for theatre workers, they have reorganised the committee structures. It used to be that funds specific to each department were allocated by a committee of experts in that area - so dance experts assessed dance, theatre practitioners assessed theatre. Now all the performing arts are lumped together on one committee. This means many committee members know little about the work they're assessing - few playwrights would be happy assessing the Scottish Dance Theatre or The Chamber Orchestra and it's rare to find a conductor who could evaluate the Traverse's educational writing programme. Nor should they. This means a less secure grip on the process by the committees, which defer more readily to Arts Council staff - presided over by Mr J. Boyle. Result, more centralised control and more lunatic decisions.

Yes, lunatic because they aren't even sticking to their own principles. TAG, despite extraordinary success in producing theatre for young people have had their funding cut in half (this also despite the SAC's stated aim of funding 'children and young people's theatre') Mull Little Theatre faces the axe. Theatre Workshop (despite great work in inclusivity and disability) also faces the axe. Borderline - about as 'audience-focused' as you can get - face the axe. We also notice that high profile touring companies are facing serious cutbacks or even being axed altogether: 7:84 and Suspect Culture being the most notable companies who must be looking to the future with trepidation.

And what's this got to do with the Scottish National Theatre? It should have nothing to do with it - after all, it was unambiguously promised the the new funding for the SNT was additional to current provision and would not affect the existing infrastructure. But, only six months on, and months and months before the SNT is likely to offer its first production, we can already see the areas that it is supposed to cover being cleared of competition - touring, geographical spread and inclusivity.

And why? Why suddenly announce these changes, with no forewarning, and with nobody who works in the sector agreeing or even being consulted (not even those untouched by cuts - the buildings)? Is it because James Boyle is a fool who can't resist fiddling with schedules? Maybe - he's certainly got form on that one. Perhaps, too, we should remember that the SAC is itself under review by the Parliament, and wants to be seen to 'get tough' with the sector. Taxpayers never complain about funding kids theatre but they do complain about funding filthy art for grown ups. This is true, though the SAC as a public body is always under scrutiny. Most likely is that the SNT risks becoming the Millenium Dome of McConnell, McAveety and Boyle - it must work or they will face the wrath of the press and taxpayers within weeks of opening. In advance of SNT, therefore, they clear the field of touring companies to give the SNT a clear run at success. This is no way for laying foundations for the SNT's long-term vitality.

But, despite that heavy-hearted parenthesis, Encore wants to acclaim the plans for a new Scottish National Theatre as the best thing to happen in 2003. May its realization be the best thing in 2004.

::

...

Best Artistic Director

2003 was runaround year for Britain's artistic directors. Nick Hytner inherited a financially, if not artistically, successful National Theatre. Michael Boyd took hold of a Royal Shakespeare Company artistically adrift in choppy financial waters. Michael Attenborough bravely agreed to follow the most successful artistic directorship of the 1990s, Jonathan Kent and Ian McDiarmid's blessed reign at the Almeida. Michael Grandage had no less a challenge, occupying the seat left vacant by jack-of-all-trades, master-of-them-all-too Sam Mendes at the Donmar. Tony Clark came from Birmingham to oversee the rebuilt Hampstead Theatre. Outside London, there were important changes, with Ian Brown bedding in at the West Yorkshire Playhouse, Simon Reade and David Farr taking the Bristol Old Vic under new management, Hamish Glen taking over the Belgrade, Coventry, and James Brining and Dominic Hill replacing him at Dundee Rep.

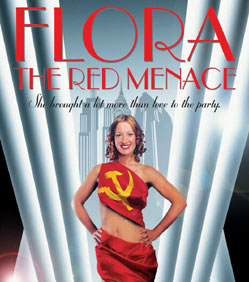

Encore's been enjoying the boldness of Farr and Reade, with two terrific Shakespeares, Comedy of Errors, and A Midsummer Night's Dream, as well as credible productions of True West and The Caretaker. The Bristol Old Vic's had more downs than ups over the last fifteen years; let's hope Bristol's audiences recognise this up and support it. Michael Grandage's first year has had at least two triumphs in Caligula and After Miss Julie as well as a bold and satisfying Hotel in Amsterdam. Brining and Hill must be credited for having reshaped the ensemble, injected energy into the building, brought in new artists, and had four critical and audience hits including a rare and fabulous revival of Kander and Ebb's Flora The Red Menace (pictured). They've made the Dundee Rep perhaps the most exciting theatre in Scotland at the moment, after The Tron. Encore's been enjoying the boldness of Farr and Reade, with two terrific Shakespeares, Comedy of Errors, and A Midsummer Night's Dream, as well as credible productions of True West and The Caretaker. The Bristol Old Vic's had more downs than ups over the last fifteen years; let's hope Bristol's audiences recognise this up and support it. Michael Grandage's first year has had at least two triumphs in Caligula and After Miss Julie as well as a bold and satisfying Hotel in Amsterdam. Brining and Hill must be credited for having reshaped the ensemble, injected energy into the building, brought in new artists, and had four critical and audience hits including a rare and fabulous revival of Kander and Ebb's Flora The Red Menace (pictured). They've made the Dundee Rep perhaps the most exciting theatre in Scotland at the moment, after The Tron.

It's too early to tell for Michael Attenborough, though there seems little sense of an identifiable artistic policy emerging at the Almeida. Hamish Glen seems to be injecting excitement into the Belgrade and Michael Boyd's cheering people up at the RSC; mind you, he's starting from a low base and it remains to be seen whether his resignation would bring Greg-Dyke-levels of public grief. Tony Clark was dealt a bad hand but did not help himself by failing to square up to the kind of policy needed for such a massively enlarged - and out-of-the-way - building as Hampstead. And then some of the programming seems to have been perverse; was there really nothing better in his mailbox than The Maths Tutor? Than Revelations?

Of course, not all the successful artistic directorships have been new; the triumvirate at Chichester quietly produced marvels over the summer; the Holman season at the Royal Exchange shone credit on everyone involved in running that wonderful building. In particular an honourable mention must go to the often-overlooked Nicolas Kent at the Tricycle: his staging of Justifying War - Scenes from the Hutton Enquiry in just the latest in a dazzling ten-year commitment to theatre as a forum for political information and debate. He has almost single-handedly revitalised the moribund tradition of documentary theatre as one of the most significant and urgent forms of contemporary British theatre. If spin represents an abuse of language (which of course it does), then Kent has consistently asked audiences to listen again to that abuse, hear in detail how lies come to resemble truths in our public discourse, how a kind of cultivated horror forms the subtext of an entire governing class. Hytner's recent announcement of a documentary drama on the reasons why we went to war in Iraq, Stuff Happens to be written by David Hare, owes much to Kent's pioneering work in tackling what John Pilger majestically called the 'normalizing of the unthinkable'. Of course, not all the successful artistic directorships have been new; the triumvirate at Chichester quietly produced marvels over the summer; the Holman season at the Royal Exchange shone credit on everyone involved in running that wonderful building. In particular an honourable mention must go to the often-overlooked Nicolas Kent at the Tricycle: his staging of Justifying War - Scenes from the Hutton Enquiry in just the latest in a dazzling ten-year commitment to theatre as a forum for political information and debate. He has almost single-handedly revitalised the moribund tradition of documentary theatre as one of the most significant and urgent forms of contemporary British theatre. If spin represents an abuse of language (which of course it does), then Kent has consistently asked audiences to listen again to that abuse, hear in detail how lies come to resemble truths in our public discourse, how a kind of cultivated horror forms the subtext of an entire governing class. Hytner's recent announcement of a documentary drama on the reasons why we went to war in Iraq, Stuff Happens to be written by David Hare, owes much to Kent's pioneering work in tackling what John Pilger majestically called the 'normalizing of the unthinkable'.

But it was undeniably Hytner's year. When was the last time that the National Theatre seemed like the most important theatre in the country?  Has this, in fact, ever happened before? Three Sisters, Mourning Becomes Electra, Jerry Springer, The Pillowman; these would be highlights of any theatregoing year. The £10 season was one of the finest things to happen in London theatre in ages. There are after show music events, playreadings during the day, there were scratch events in protest at the Iraq misadventure. There are new collaborations, new artists working there, a genuine sense rippling through the theatre community that the National is excited by what it doesn't yet know about. Thinking back did anyone see a flop at the National this year? Did anyone see anything that wasn't finally well worth doing? No doubt 2004 will bring the stupid backlash, so let's remember that 2003 was a year of intensely exciting work at the National, produced in a new atmosphere of creativity and originality, all under Hytner's coolly politicised gaze. It had to be him. Encore's award for the artistic director of 2003 goes to Has this, in fact, ever happened before? Three Sisters, Mourning Becomes Electra, Jerry Springer, The Pillowman; these would be highlights of any theatregoing year. The £10 season was one of the finest things to happen in London theatre in ages. There are after show music events, playreadings during the day, there were scratch events in protest at the Iraq misadventure. There are new collaborations, new artists working there, a genuine sense rippling through the theatre community that the National is excited by what it doesn't yet know about. Thinking back did anyone see a flop at the National this year? Did anyone see anything that wasn't finally well worth doing? No doubt 2004 will bring the stupid backlash, so let's remember that 2003 was a year of intensely exciting work at the National, produced in a new atmosphere of creativity and originality, all under Hytner's coolly politicised gaze. It had to be him. Encore's award for the artistic director of 2003 goes to

Nick Hytner (National Theatre, London)

Runners-up:

Michael Grandage (Donmar, London)

Simon Reade and David Farr (Bristol Old Vic)

James Brining and Dominic Hill (Dundee Rep)

Nicolas Kent (Tricycle)

::

...

Best Lighting

Lighting gave us a series of extraordinary boat trips in 2003. In the RSC's Brand (Haymarket Theatre, London), Peter Mumford showed us Brand and Agnes's perilous journey out onto the fjords through colour: a deep blue, with aquamarine lifting the figures, before plunging them, as the danger deepened and the shore receded, into an intense, saturated, almost Yves Klein, electric blue. At the other end of the year, Paule Constable's work on His Dark Materials (National: Olivier) threw some of her trademark open white light behind a rowing boat that spiralled up out of the stage, oars cutting furious shadows into the glare, to convey the narrative into hell. Meanwhile Mark Henderson did his dutiful part in converting the set into an ocean liner for the finale of the very stupid Tonight's the Night (Victoria Palace, London).

There were impressive inroads into theatrical lighting from designers, like Mumford, who despite being spoiled in opera showed a sensitivity to lighting for narrative, mood, character. Wolfgang Goebbel's sleek catwalk for Power at the National's Cottesloe stage was restrained and largely effective (I say 'largely' because of a limp forework display that scarcely looked likely to outshine the Sun King). But perhaps more interesting was the influx from the other direction: designers emerging from live art, performance and dance, who bring an edgy sense of lighting as the most mercurial theatre technology. A good example was Nigel Edwards's design for Sexual Perversity in Chicago (Comedy Theatre, London) which worked at least as effectively as the set did to create sudden cinematic cutaways, prompting the characters into speech, Beckett-like, with the imperious stare of a lantern. Edwards is a veteran of Forced Entertainment's work and the sense of theatrical possibility, as well as a witty sense of its plasticity was always joyfully at the heart of this work. Chahine Yavroyan is no newcomer but she also brought a sensibility at least partly weaned on site-specific work and performance to San Diego at the Lyceum, subjecting the action to a wonderfully unblinking Californian sun. Colin Grenfell did some wonderful subtle and atmospheric work on Improbable's The Hanging Man (touring) despite the notoriously last-minute and improvisatory nature of the company's creative development, usually antipathetic to the lighting designer's need for clear scheduling and much advance notice.

Nonetheless, the most high profile lighting venues continue to be dominated by a few familiar names. Rick Fisher's work this year has been effective without being flamboyant. Mark Henderson oversaw the National's ?10 Olivier season, and his Henry V used intensely-coloured light to stain the smoke of war blood-red in a large-scale, open and epic space.  As good was his work on Edmond where the picaresque wanderings of the protagonist threw him into a series of locations only minimally picked out by the set but sharply drawn by fluid and imaginative changes in light. His Girl Friday, like his Democracy (National: Cottesloe) later in the year, was hemmed in by a rather restrictrive set and the on-stage lanterns looked decorative rather than integrated. His contribution to Mourning Becomes Electra (National: Lyttelton, pictured), however, was something else again. A bleached and unremitting palette of colours beat down on this tragedy, and swept the characters to the denouement. And what a denouement; Eve Best as Lavinia, the last remaining member of the doomed Mannon family, having seen the destruction of her father, mother, and brother, retreats into the family mansion. Bob Crowley's grand crumbling ruin swept across the stage, reforming as a long high corridor. As Best pushed open the door, the blood-red of the walls were battered out by a cruel deep blue that turned the passion to ice; as Best sinks to the ground, by now virtually a silhouette, Henderson has made the house into a tomb and it's his lighting, as much as Crowley's or Best's work, that shows us the full horror of the death that may be endured by the living. As good was his work on Edmond where the picaresque wanderings of the protagonist threw him into a series of locations only minimally picked out by the set but sharply drawn by fluid and imaginative changes in light. His Girl Friday, like his Democracy (National: Cottesloe) later in the year, was hemmed in by a rather restrictrive set and the on-stage lanterns looked decorative rather than integrated. His contribution to Mourning Becomes Electra (National: Lyttelton, pictured), however, was something else again. A bleached and unremitting palette of colours beat down on this tragedy, and swept the characters to the denouement. And what a denouement; Eve Best as Lavinia, the last remaining member of the doomed Mannon family, having seen the destruction of her father, mother, and brother, retreats into the family mansion. Bob Crowley's grand crumbling ruin swept across the stage, reforming as a long high corridor. As Best pushed open the door, the blood-red of the walls were battered out by a cruel deep blue that turned the passion to ice; as Best sinks to the ground, by now virtually a silhouette, Henderson has made the house into a tomb and it's his lighting, as much as Crowley's or Best's work, that shows us the full horror of the death that may be endured by the living.

Paule Constable was busy. Her work on Jumpers (National: Lyttleton & Piccadilly Theatre, London) was as messy and incoherent as the play and the production, though was not without wit. Perhaps she was the wrong designer for this; Constable is a great one for the austerity of spotlight, finding and isolating areas and corners (seen at its best in Camille at the Lyric Hammersmith) but Jumpers was a play in need of some grand washes to bring it all together. Pericles (also Lyric Hammersmith) was perhaps just a little too harsh; the combination of Bartlett's beautifully severe classicism and Constable's love of par cans - okay, I'm being frivolous now - worked a bracing treat on The Prince of Homburg a couple of years ago, but here it seemed cold. But her finest moment was Three Sisters (pictured) at the Lyttelton; working with a faded, limpid green, pale yellow palette, a real sense of long-lived life echoed through the sisters' home.  The world beyond the house was as thrillingly realised as the world within, and the tones and hues that graduated throughout the design were hauntingly precise and aching in their emotional richness. This was rare work. The world beyond the house was as thrillingly realised as the world within, and the tones and hues that graduated throughout the design were hauntingly precise and aching in their emotional richness. This was rare work.

Lighting technology continues to develop cleaner, more precise, sharper and more manipulable lanterns, though no massive breakthroughs were visible last year, and interest continues to be channelled towards projected settings which, however interesting in themselves, impose horrible restrictions on the lighting designer's art. Hitchcock Blonde (Royal Court Downstairs & Lyric Theatre, London) was a good example here; Bill Dudley's invasive animated projections gave Simon Corder little to do, though the DV8-inspired projection on water was magical. There are exciting things to be done in CGI - two years ago in Stoppard's trilogy, we had another boat trip, as the great cyc took us by river out of Moscow from the point of view of the prow, and the effect was breathtaking, immersive, epic. But there remains something elementally beautiful in the way a single light can lift an actor out of the darkness.

This is why we have chosen Hugh Vanstone as Encore's lighting designer of the year. Partly this is for his work on his fine work on The Pillowman with high beams interrogating the hapless writer, grimly enhancing the gun metal tones of the prison walls, alongside the witty cutaways into the storybook world; judicious unreality underscoring the unsettled world of the imagination. But mainly it is for The Lady from the Sea (pictured) that we offer this award. Opening the new, improved Almeida with this feast of colour, texture, of dappled light that suggested the waters sparkling around the characters even before myth takes hold of their hearts. Theatre light has that ability sometimes to make you forget where you are, to allow that dreamstate to take over, and here we forgot the vulgarity of this wealthy powerful audience, because here were theatrical pictures, rich in mood, simple, beautiful, magnificent. This is why we have chosen Hugh Vanstone as Encore's lighting designer of the year. Partly this is for his work on his fine work on The Pillowman with high beams interrogating the hapless writer, grimly enhancing the gun metal tones of the prison walls, alongside the witty cutaways into the storybook world; judicious unreality underscoring the unsettled world of the imagination. But mainly it is for The Lady from the Sea (pictured) that we offer this award. Opening the new, improved Almeida with this feast of colour, texture, of dappled light that suggested the waters sparkling around the characters even before myth takes hold of their hearts. Theatre light has that ability sometimes to make you forget where you are, to allow that dreamstate to take over, and here we forgot the vulgarity of this wealthy powerful audience, because here were theatrical pictures, rich in mood, simple, beautiful, magnificent.

Hugh Vanstone The Lady from the Sea (Almeida, London)

Runners-up:

Paule Constable Three Sisters (National: Lyttelton)

Mark Henderson Mourning Becomes Electra (National: Lyttelton)

Peter Mumford Brand (RSC: Haymarket)

::

...

Best Design

2003 taught us the value of austerity in design. Some of the most abysmal trash of the year came decked out in magnificent clothes; look no further than Lez Brotherston’s designs for Tonight’s the Night: The Rod Stewart Musical (Victoria Palace Theatre), which included a flying bed and a finale in which the ‘Gasoline Alley’ set transforms into the HMS Penny for a full-cast singalong of ‘Sailing’. Julian Crouch’s hellbound second half of Jerry Springer - The Opera (National: Lyttelton, and West End) is just garish, where the first half was well-observed and wittily restrained. His designs for The Hanging Man (Improbable) on the other hand were a delight: gaudy, gothic and grand, a kind of theatrical magic chest that opened on another world of delight.

There were spectacular designs that delighted this year; Giles Cadle and Michael Curry incarnated the world of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy and the creatures that inhabit it with restraint and power. Bob Crowley’s fading mansion for Mourning Becomes Electra’s transformed into the oak-panelled labyrinth within (and even became a ship, though with a kind of dramatic power and purpose that Tonight’s the Night can only dream at). There were spectacular designs that delighted this year; Giles Cadle and Michael Curry incarnated the world of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy and the creatures that inhabit it with restraint and power. Bob Crowley’s fading mansion for Mourning Becomes Electra’s transformed into the oak-panelled labyrinth within (and even became a ship, though with a kind of dramatic power and purpose that Tonight’s the Night can only dream at).

Our designers continued to flirt with digital media, most inessentially in William Dudley’s Hitchcock Blonde (Royal Court), where the three-dimensional CGI models only contributed to the sense of superficiality and the visual clutter of the piece. Rather better was the Lightwall created for Peter Stein’s otherwise disappointing The Seagull (King’s Theatre, Edinburgh): a huge screen, the size of the rear wall which, tilted this was and that, swirled with colour, especially in the final act as a rumble of smoky darkness threatened to shut out the light.

More traditional virtues were to be found in Rob Howell’s gorgeous sets for The Lady from the Sea which showed off the Almeida’s improved stage technology while still respecting its traditional brick backdrop; the locations were evocative, atmospheric, mysterious as the play. Vicki Mortimer’s dazzling sets for Three Sisters (National: Lyttelton) had a monumental beauty - great high ceilings, age-yellowed walls and fragile windows - but were fully practical too, utterly actable: these were spaces with history, rooms for those lives to dwindle in.

But it was a year where the most telling designs used minimalism, abstraction, clarity. It was rumoured that the extravagance of His Dark Materials was bought at the expense of the rest of the year’s design budgets, but actually the National’s designers did their best work on more limited means: Alison Chitty placed Scenes from the Big Picture in a blue box (pictured); the furniture and prop stacked up at the rear of the space encouraged us to see the big picture that accumulated around these scenes. The Pillowman (Scott Pask), also in the Cottesloe, played most of the action in a chilling and dark dungeon, the high walls only occasionally windowing out to show us the cruelties of a writer’s imagination. The best two shows in the £10 season were Henry V (Tim Hatley) and Edmond (Michael Pavelka), both of which stripped the Olivier back to a kind of huge studio arena, giving both productions an epic clarity. Neither Peter J Davison’s maisonette-work for Democracy, nor Vicki Mortimer’s junk-shop Jumpers served their productions, the designs appearing too self-involved and insufficiently organised, respectively. But it was a year where the most telling designs used minimalism, abstraction, clarity. It was rumoured that the extravagance of His Dark Materials was bought at the expense of the rest of the year’s design budgets, but actually the National’s designers did their best work on more limited means: Alison Chitty placed Scenes from the Big Picture in a blue box (pictured); the furniture and prop stacked up at the rear of the space encouraged us to see the big picture that accumulated around these scenes. The Pillowman (Scott Pask), also in the Cottesloe, played most of the action in a chilling and dark dungeon, the high walls only occasionally windowing out to show us the cruelties of a writer’s imagination. The best two shows in the £10 season were Henry V (Tim Hatley) and Edmond (Michael Pavelka), both of which stripped the Olivier back to a kind of huge studio arena, giving both productions an epic clarity. Neither Peter J Davison’s maisonette-work for Democracy, nor Vicki Mortimer’s junk-shop Jumpers served their productions, the designs appearing too self-involved and insufficiently organised, respectively.

Elsewhere, Ian McNeil’s split-level Peribanez (Young Vic) cut through any fusty period trappings to nicely underscore the class and caste levels of Lope de Vega’s play. Peter McKintosh enclosed the RSC Brand in a forbidding and austere high, wooden semicircle, which lifted up to reveal a wall of icy smoke that slowly and massively collapsed down on us to provide the play’s climactic avalanche. Simon Vincenzi’s gave us San Diego (King’s Theatre and Tron) in a Californian white-out, studded with suitcases on wheels, a wonderful visual metaphor for the global individualism of the characters. Ultz turned the Royal Court downstairs into a bear pit for Fallout, the clinical whiteness and wire cages giving focus to the frustrated longings of the characters.

Christopher Oram had a good year; he gave us a powerful traverse staging of Power (National: Cottesloe) allowing the courtiers of the Sun King to strut on a pre-revolutionary catwalk. For A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Crucible, Sheffield, pictured), he placed the action on bare boards, lit by a vast unblinking midsummer moon, giving the language space to work its madness. And for the Donmar’s Caligula he gilded a brick wall which shimmered and glowered in the light, a surface shot through with colour like a petrol slick on a wet road. It caught the surfaces of power, the brilliance and horror of rational tyranny, the emperor’s mixture of dazzling insight and flashing anger. The rest of the stage was left empty, apart from an elemental moment where a mirror is lifted from a pool to prompt further bottomless reflection on the grounds and ends of being and doing. It was a beautiful design, clear, magnificent and it stamped the production with cruelly dazzling authority. This was Encore’s design of the year. Christopher Oram had a good year; he gave us a powerful traverse staging of Power (National: Cottesloe) allowing the courtiers of the Sun King to strut on a pre-revolutionary catwalk. For A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Crucible, Sheffield, pictured), he placed the action on bare boards, lit by a vast unblinking midsummer moon, giving the language space to work its madness. And for the Donmar’s Caligula he gilded a brick wall which shimmered and glowered in the light, a surface shot through with colour like a petrol slick on a wet road. It caught the surfaces of power, the brilliance and horror of rational tyranny, the emperor’s mixture of dazzling insight and flashing anger. The rest of the stage was left empty, apart from an elemental moment where a mirror is lifted from a pool to prompt further bottomless reflection on the grounds and ends of being and doing. It was a beautiful design, clear, magnificent and it stamped the production with cruelly dazzling authority. This was Encore’s design of the year.

Christopher Oram Caligula (Donmar, London)

Runners-up:

Rob Howell The Lady from the Sea (Almeida)

Vicki Mortimer Three Sisters (National: Lyttelton)

Ultz Fallout (Royal Court)

:: Theatre Worker Saturday, January 03, 2004 [+] ::

...

Best New Play

Virtually no good new plays were produced in London this year. The Royal Court's programming continued to be shameful. Flesh Wound and Food Chain were desperately forgettable. Hitchcock Blonde was stronger but the Court seemed interested in it purely as a money-spinner and had evidently not encouraged Terry Johnson to decide which play he was writing. Roy Williams's Fallout was given a strong production by the aimless Ian Rickson, but this only disguised the play's well-meaning but flabby dramatic qualities. Richard Bean's Under the Whaleback was better but it was ruined by a Royal-Court-by-numbers third act with its foolish device of stapling a man's hands to a table, thus robbing him of half of his expressivity and most of his ability to create new drama. Richard Bean wrote better for the Bush and more vigorously for the Live Theatre in Newcastle, so we suspect some unwelcome dramaturgical tampering. The most thrilling was Terrorism by the Presnyakov brothers: the production started appallingly, shepherding the audience around like in some earnest A-Level drama project, but from there got better and better, with allusions and echoes rippling across the play's surface to create a vivid theatrical magic. But the play premiered in Moscow last year and is ineligible. The most exciting new voice this year was Debbie Tucker Green, whose Born Bad (Hampstead) and Dirty Butterfly (Soho) reminded us of everything that the Court has turned its back on: urgent sensitivity to language, metaphor, formal experiment, an impatience with artistic compromise, and a rigorous desire to tell new stories.

Some of our major institutions and writers have no idea how to write political plays. The Court's pointless policy of reflecting real life without comment or creativity was outclassed by the documentary drama at the Tricycle. Justifying War (soon due for broadcast on BBC4) was a better piece of political commentary and service than anything at the Court.  It was certainly better than Tariq Ali's risible piece of political farce, The Illustrious Corpse (Leicester Haymarket), puffed up in the New Statesman as the inheritance of Piscator, Brecht, and Dario Fo. In your pinched dreams, sunshine. David Hare's docu-drama The Permanent Way (Out of Joint) was better, if aimed at a soft target, but at least suggested a sense of theatre as a medium in which people understand truths together. Hare inspired Neil LaBute's very unsatisfying The Mercy Seat (Almeida), as vacuous a piece of handwringing as we saw on the stage this year. The National misfired with two plays that seemed to be attempting an analysis of our current politics: Nick Dear's beautifully-written Power was a hypnotic and hilarious study of the court of the Sun King, but we waited on the edge of our seats for the links to current power politics really to have bite, but the bite never came. The same was true of Michael Frayn's Democracy (pictured), which revisited some of the dramatic devices of his glorious Copenhagen, but this time remained sunk in the research. Encore was divided on the merits of the play? Was this love letter to Willy Brandt codedly about Tony Blair? Was it about betrayal? The politics of image? The love between enemies? Or was it just a love letter to Willy Brandt? Or, worse, a love letter to Michael Frayn's bibliography of Willy Brandt? It was certainly better than Tariq Ali's risible piece of political farce, The Illustrious Corpse (Leicester Haymarket), puffed up in the New Statesman as the inheritance of Piscator, Brecht, and Dario Fo. In your pinched dreams, sunshine. David Hare's docu-drama The Permanent Way (Out of Joint) was better, if aimed at a soft target, but at least suggested a sense of theatre as a medium in which people understand truths together. Hare inspired Neil LaBute's very unsatisfying The Mercy Seat (Almeida), as vacuous a piece of handwringing as we saw on the stage this year. The National misfired with two plays that seemed to be attempting an analysis of our current politics: Nick Dear's beautifully-written Power was a hypnotic and hilarious study of the court of the Sun King, but we waited on the edge of our seats for the links to current power politics really to have bite, but the bite never came. The same was true of Michael Frayn's Democracy (pictured), which revisited some of the dramatic devices of his glorious Copenhagen, but this time remained sunk in the research. Encore was divided on the merits of the play? Was this love letter to Willy Brandt codedly about Tony Blair? Was it about betrayal? The politics of image? The love between enemies? Or was it just a love letter to Willy Brandt? Or, worse, a love letter to Michael Frayn's bibliography of Willy Brandt?

Three of the most interesting plays this year shared a common subject matter. Richard Bean's The God Botherers (Bush), Sonja Linden's I Have Before Me A Remarkable Document Given to Me by A Young Lady From Rwanda (Finborough), and Steve Waters's World Music (Sheffield Crucible) all concerned themselves with the politics of Western aid and the clash of liberal idealism with the complexities of conflict in the developing world. Richard Bean's was knockabout stuff, though forceful in its wilful disregard of taboos; Linden's play addressed the political through the personal with a kind of roughness that made the issues wholly irresistible. Steve Waters's play was the most profoundly compelling of them all, bitterly funny, elegantly constructed, bold in conception, and rightly heading for the Donmar in 2004.

This year we longed for metaphor. Political playwriting isn't just in the documentary record of current events, it's in the evocation of other lives, of our common bonds, of worlds we might live in, and aspirations we'd forgotten to pursue. As our imaginations are trampled by entertainment and our utopias crowded out by commerce, the theatre's ability to create new collective dreams becomes more and more important. In a jaded age, a theatre that isn't visionary isn't worth visiting. There were very few plays with vision, plays that offered us new thoughts, new intensities of experience, plays whose beauty stopped the breath in our mouths. Kay Adshead's Animal was a weird, intoxicating, whirlwind of a play, imagining a future or a present of riots, universal confinement, human experimentation and a great natural revolt. It was flawed, sure, what play like that wouldn't be flawed? But it was exciting and vivid and rewarding, and better a flawed Animal (Soho Theatre) than a word-perfect The Straits. Howard Barker's best play and production for ages, 13 Objects (Wrestling School), organised its author's untameable poetic hunger in a series of thirteen hilarious, profound, unsettling vignettes; a woman defiantly drinking coffee in the same cafe she once visited with her departed lover, a tyrannical baby throwing a rattle out of its pram, someone's horror at being photographed, a millionaire benevolently saving a Holbein from commercialisation by destroying it. What would we have done without Howard Barker, saving us from mediocrity this last thirty years? Martin McDonagh surprised with the riveting and thrilling The Pillowman, creating a whole dystopian world within a world; his storyteller was beautifully drawn, and his grim(m) stories had that authentic stink of brutality, torture and the supernatural that you find in those European fairytales.

But Encore's play of the year was not seen in London. Nor, to the shame of all our national institutions, does it look at all likely that it will be. Highlight of this year Edinburgh International Festival, David Greig's San Diego (pictured).  This was a massive play, jetting across the world, interweaving a large number of individually fascinating stories in a rich whole. It was about a search for parenthood, the voraciousness of love, the connections we form across the world, the sublime banality of Hollywood, our need to beat away the natural world, and the eternal search for home. Building on the fragmentary-but-unified style of the same author's earlier The Cosmonaut's Last Message..., but this time narrated by 'David Greig', a quasi-authorial, omnimpotent figure, splintered throughout the play, dying and reappearing, with the world spinning around him. There was a wealth of humour in the play - two illegal immigrants solemnly singing "Band on the Run" at the improvised funeral of their adopted son, a charming joker in a psychiatric hospital, a wonderful pastiche of a disaster movie; but there was also passion in a pilot's savage denunciation of a vacuous rebranding exercise and in a woman's exquisite evocation of love: "I feel like I've suddenly fallen into the arms of an old, old city. Rome. He's Rome and I'm a Roman." It's a magnificent speech, reminiscent of Sarah Kane's ambivalent passion, but with Greig's unique stamp. The play was deprecated by some critics - we can only hope that, one day, in some late hour of the night, John Peter will realise his unsuitedness to the modern world, let alone the contemporary theatre, and fax an irretrievable resignation letter to the Sunday Times - but that's inevitable given the state of our critics. It was a big production, no doubt an expensive production, but it would have transferred beautifully to the Royal Court, the National, the Lyric, Hammersmith maybe. Yes it would have been a risk, but if safety is Fallout, let's take risks. For its vision, its beauty, its breathtaking evocation of our worldwide commitments and concerns, the Encore award for Best New Play 2003 goes to: This was a massive play, jetting across the world, interweaving a large number of individually fascinating stories in a rich whole. It was about a search for parenthood, the voraciousness of love, the connections we form across the world, the sublime banality of Hollywood, our need to beat away the natural world, and the eternal search for home. Building on the fragmentary-but-unified style of the same author's earlier The Cosmonaut's Last Message..., but this time narrated by 'David Greig', a quasi-authorial, omnimpotent figure, splintered throughout the play, dying and reappearing, with the world spinning around him. There was a wealth of humour in the play - two illegal immigrants solemnly singing "Band on the Run" at the improvised funeral of their adopted son, a charming joker in a psychiatric hospital, a wonderful pastiche of a disaster movie; but there was also passion in a pilot's savage denunciation of a vacuous rebranding exercise and in a woman's exquisite evocation of love: "I feel like I've suddenly fallen into the arms of an old, old city. Rome. He's Rome and I'm a Roman." It's a magnificent speech, reminiscent of Sarah Kane's ambivalent passion, but with Greig's unique stamp. The play was deprecated by some critics - we can only hope that, one day, in some late hour of the night, John Peter will realise his unsuitedness to the modern world, let alone the contemporary theatre, and fax an irretrievable resignation letter to the Sunday Times - but that's inevitable given the state of our critics. It was a big production, no doubt an expensive production, but it would have transferred beautifully to the Royal Court, the National, the Lyric, Hammersmith maybe. Yes it would have been a risk, but if safety is Fallout, let's take risks. For its vision, its beauty, its breathtaking evocation of our worldwide commitments and concerns, the Encore award for Best New Play 2003 goes to:

David Greig San Diego (Lyceum Theatre & Tron)

Runners-up:

Martin McDonagh The Pillowman

David Harrower Dark Earth

Debbie Tucker Green Dirty Butterfly and Born Bad

Kay Adshead Animal

::

...

Best Revival

This was a strong year for revivals, with some excellent offerings in all the major theatres. What was especially pleasing was the growing recognition of the modern repertoire in the major theatres;  John Osborne's A Hotel in Amsterdam was handsomely revived at the Donmar, under Robin Lefevre's direction and with a searing central performance by Tom Hollander. Intriguingly, no one who watched the play can have wondered at the lack of any revivals since 1968: the play is poorly carpentered in places - the ending tried cheaply to bring the curtain down on a thrill of guilty horror - and, as is not unusual in Osborne, only the central character is painted with much psychological penetration. But it lived on that stage, it burned. And the saving grace of the ending is that it turned this nakedly autobiographical play against its author with cold fury. There were two Robert Holman revivals up at the Royal Exchange, Manchester, alongside a raft of readings; both shone. Rafts and Dreams was revealed as a rich, bold, visionary masterpiece, and Across Oka was displayed with love, gentle perception and abyssal emotional richness. It was good, too, to see Chris Hannan's Shining Souls (pictured), reupholstered and revisited in a melancholy, beautiful and vigorous production by V.amp at the Tron. John Osborne's A Hotel in Amsterdam was handsomely revived at the Donmar, under Robin Lefevre's direction and with a searing central performance by Tom Hollander. Intriguingly, no one who watched the play can have wondered at the lack of any revivals since 1968: the play is poorly carpentered in places - the ending tried cheaply to bring the curtain down on a thrill of guilty horror - and, as is not unusual in Osborne, only the central character is painted with much psychological penetration. But it lived on that stage, it burned. And the saving grace of the ending is that it turned this nakedly autobiographical play against its author with cold fury. There were two Robert Holman revivals up at the Royal Exchange, Manchester, alongside a raft of readings; both shone. Rafts and Dreams was revealed as a rich, bold, visionary masterpiece, and Across Oka was displayed with love, gentle perception and abyssal emotional richness. It was good, too, to see Chris Hannan's Shining Souls (pictured), reupholstered and revisited in a melancholy, beautiful and vigorous production by V.amp at the Tron.

Of the more established living playwrights, Mamet fared best; Edmond (National) and Sexual Perversity in Chicago (Comedy Theatre, London) reminded us why he is the greatest single influence on British playwriting over the last decade. Edmond, in particular, looked like the play that has haunted British stages for years, and you kept thinking of Ravenhill, Penhall, Marber, Crimp. David Hare's late-eighties trilogy was stoutly offered in Birmingham in productions that struggled to hide these plays' defects. Racing Demon, Hare's best and funniest play, came off okay, though Murmuring Judges seemed just as inept, and The Absence of War just as shallow, as they seemed a decade ago. Meanwhile, Harriet Walter was haunting in an otherwise inessential revival of Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea.

Comedy fared less well; the Donmar's Accidental Death of an Anarchist was an uproarious experience, thanks to Rhys Ifans rather more than Dario Fo, who famously improvised around his script for years but has now unwisely set it in stone. Simon Nye proved not to be a King Arthur here, offering a wordy, muddy version in which the real political impact remained resolutely out of grasp.  The National's His Girl Friday was comically underpowered, too, Alex Jennings seeming a little stiff for the play's moral gymnastics. The Traverse's commemorative revival of John Byrne's Slab Boys trilogy certainly reminded us of the play's greatness, but it was a rather wintry experience. Simon Russell Beale shone as ever in Stoppard's Jumpers, but it was a visually fragmented production and this wildly centrifugal play needed something more contained to marshal its verbal energies. The National's His Girl Friday was comically underpowered, too, Alex Jennings seeming a little stiff for the play's moral gymnastics. The Traverse's commemorative revival of John Byrne's Slab Boys trilogy certainly reminded us of the play's greatness, but it was a rather wintry experience. Simon Russell Beale shone as ever in Stoppard's Jumpers, but it was a visually fragmented production and this wildly centrifugal play needed something more contained to marshal its verbal energies.

But it was naturalism's year. If you had never seen an Ibsen play, some assiduous theatregoing would have given you the chance to catch up on at least nine of them. Some were excellent: the Almeida's Lady from the Sea (pictured) was heart-stopping in its beauty and driving narrative horror. English Touring Theatre's John Gabriel Borkman struggled against the Paul Scofield's definitive reading only a few years ago but still battled through the snow to produce a horrifying vision of a Nietzschean overman, reaching for the heights. Pernilla August was radiant in Ingmar Bergman's Ghosts (BITE). The philosophical austerities of Brand, however, were ill-suited to the vile opulence of the Haymarket and the fancy trick ending was not enough to make you feel that this play lived on the stage. Strindberg did rather better than usual in a starry West End Dance of Death and Patrick Marber's respectfully-titled After Miss Julie.

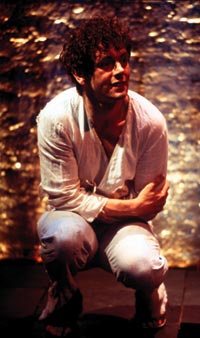

But Chekhov, once again, held the stage. Not because of the Oxford Stage Company's amateurish touring Cherry Orchard, or Peter Stein's half-hearted The Seagull (King's Theatre, Edinburgh Festival), and certainly not the appalling Michael-Blakemore-directed Three Sisters at the Playhouse. But because of the greatest Chekhov production of the last decade, Katie Mitchell's hypnotic, terrifying Three Sisters at the National's Lyttelton Theatre. The play unfolded at the pace of its characters' days; the stage was filled with activity, thought, the texture of these people's lives. The play was strongly rethought, especially in its last act, but to profound effect; Irina, in this production, really is about to go to Moscow, and the final collapse of this hope collapsed with her body, dissolved heartbreakingly among her luggage. The set was beautiful, creating a depth and texture for these sisters truly to inhabit, wanly illuminated by Paule Constable's bold and gentle lighting that immersed these drained spirits in a watery halo. And then the cast; Lucy Whybrow managed to repel and demand our sympathy as the ascendant Natasha; Ben Daniels's Vershinin and Angus Wright's Kulygin dispelled years of British tradition that have transformed these figures into stock figures; the dashing sergeant and the bookish cuckold became figures of hope and righteous fury. The sisters acted, as they must, with cruelty and sentiment, with sisterly love and egoistic contempt. Anna Maxwell Martin and Lorraine Ashbourne showed us with an honesty that caught your breath the sense of human need that floundered around in search of someone or something to love, to commit to. But it was Eve Best's evening (pictured). Somehow she managed to seem alternately radiant and drained, full of mischief and life, and wholly bereft of all spirit. She was flirtatious, she was prim, she was censorious, she was freethinking. She gave Masha the kind of independent life that we can play and play again in our memories. It was simply one of those performances; unforgettable, unrepeatable, endlessly revealing. The production gave the play back to us after years of star vehicles, of limp nostalgia, of a Chekhov forgotten behind frocks and fans, and for that reason, Encore's award for Best Revival of 2003 goes to: But Chekhov, once again, held the stage. Not because of the Oxford Stage Company's amateurish touring Cherry Orchard, or Peter Stein's half-hearted The Seagull (King's Theatre, Edinburgh Festival), and certainly not the appalling Michael-Blakemore-directed Three Sisters at the Playhouse. But because of the greatest Chekhov production of the last decade, Katie Mitchell's hypnotic, terrifying Three Sisters at the National's Lyttelton Theatre. The play unfolded at the pace of its characters' days; the stage was filled with activity, thought, the texture of these people's lives. The play was strongly rethought, especially in its last act, but to profound effect; Irina, in this production, really is about to go to Moscow, and the final collapse of this hope collapsed with her body, dissolved heartbreakingly among her luggage. The set was beautiful, creating a depth and texture for these sisters truly to inhabit, wanly illuminated by Paule Constable's bold and gentle lighting that immersed these drained spirits in a watery halo. And then the cast; Lucy Whybrow managed to repel and demand our sympathy as the ascendant Natasha; Ben Daniels's Vershinin and Angus Wright's Kulygin dispelled years of British tradition that have transformed these figures into stock figures; the dashing sergeant and the bookish cuckold became figures of hope and righteous fury. The sisters acted, as they must, with cruelty and sentiment, with sisterly love and egoistic contempt. Anna Maxwell Martin and Lorraine Ashbourne showed us with an honesty that caught your breath the sense of human need that floundered around in search of someone or something to love, to commit to. But it was Eve Best's evening (pictured). Somehow she managed to seem alternately radiant and drained, full of mischief and life, and wholly bereft of all spirit. She was flirtatious, she was prim, she was censorious, she was freethinking. She gave Masha the kind of independent life that we can play and play again in our memories. It was simply one of those performances; unforgettable, unrepeatable, endlessly revealing. The production gave the play back to us after years of star vehicles, of limp nostalgia, of a Chekhov forgotten behind frocks and fans, and for that reason, Encore's award for Best Revival of 2003 goes to:

Three Sisters (National: Lyttelton, dir. Katie Mitchell).

Runners-up:

Lady From the Sea (Almeida, dir, Trevor Nunn)

A Hotel in Amsterdam (Donmar, dir. Robin Lefevre)

Shining Souls (V.amp - Tron, dir. Alison Peebles)

Rafts and Dreams (Royal Exchange, dir. Tim Stark)

::

...

|

A few theatre managements have contrived to defy the architectural horrors they were bequeathed: the success of the Lyric Hammersmith is to do with Neil Bartlett's wonderful programming, which manages to attract a huge and diverse audience to each production; it's certainly not the ambience of its first floor foyer, a misguided exercise in burolandschaft. With luck the redevelopment will allow the architecture to reach the standard of the audience and the policy. The National has introduced some well-placed lighting installations to liven up the general brutality; again, as with the Lyric, it's the buzz of the audience that has really transformed the feel of the building. The Battersea Arts Centre has a good cafe but the building as a whole hasn't been able to throw off its aura of municipal sternness. The new Hampstead theatre is an improvement on the last but it's felt rather a drafty place whenever Encore's been there; a space that cavernous really needs a throng.

So, there's not much the celebrate in London. There are good examples of theatres that genuinely seem to reach out to their communities around the country - the West Yorkshire Playhouse is a good example. But some of the theatres most celebrated for their accessibility and inclusiveness are complacent about their audience's comfort: The Citz is a good example - the foyer's a mess, the beer is fantastically expensive, and they're going to ban smoking. No one has ever called the Tramway inclusive, but why don't they do something about that amenity-free wind tunnel of a foyer?

So many moments stand out, but Encore particularly admired the conversation between Lyngstrand and Bolette on the duties of a wife.

The blame for this lies can be largely laid at the feet of James Boyle (right), who is proving about as popular at the SAC as he was at Radio 4, and is now cosying up with the Scottish Executive and the macho West Coasters in Holyrood, Frank McAveety (arts minister who loves football more than art) and Jack McConnell (never yet seen at the theatre). This trio have decided that the new priorities are: 'audience-focused' work (meaning populism), and 'children and young people' (meaning educational work that can go into schools without ruffling any feathers).

Encore's been enjoying the boldness of Farr and Reade, with two terrific Shakespeares, Comedy of Errors, and A Midsummer Night's Dream, as well as credible productions of True West and The Caretaker. The Bristol Old Vic's had more downs than ups over the last fifteen years; let's hope Bristol's audiences recognise this up and support it. Michael Grandage's first year has had at least two triumphs in Caligula and After Miss Julie as well as a bold and satisfying Hotel in Amsterdam. Brining and Hill must be credited for having reshaped the ensemble, injected energy into the building, brought in new artists, and had four critical and audience hits including a rare and fabulous revival of Kander and Ebb's Flora The Red Menace (pictured). They've made the Dundee Rep perhaps the most exciting theatre in Scotland at the moment, after The Tron.

Of course, not all the successful artistic directorships have been new; the triumvirate at Chichester quietly produced marvels over the summer; the Holman season at the Royal Exchange shone credit on everyone involved in running that wonderful building. In particular an honourable mention must go to the often-overlooked Nicolas Kent at the Tricycle: his staging of Justifying War - Scenes from the Hutton Enquiry in just the latest in a dazzling ten-year commitment to theatre as a forum for political information and debate. He has almost single-handedly revitalised the moribund tradition of documentary theatre as one of the most significant and urgent forms of contemporary British theatre. If spin represents an abuse of language (which of course it does), then Kent has consistently asked audiences to listen again to that abuse, hear in detail how lies come to resemble truths in our public discourse, how a kind of cultivated horror forms the subtext of an entire governing class. Hytner's recent announcement of a documentary drama on the reasons why we went to war in Iraq, Stuff Happens to be written by David Hare, owes much to Kent's pioneering work in tackling what John Pilger majestically called the 'normalizing of the unthinkable'.

Has this, in fact, ever happened before? Three Sisters, Mourning Becomes Electra, Jerry Springer, The Pillowman; these would be highlights of any theatregoing year. The £10 season was one of the finest things to happen in London theatre in ages. There are after show music events, playreadings during the day, there were scratch events in protest at the Iraq misadventure. There are new collaborations, new artists working there, a genuine sense rippling through the theatre community that the National is excited by what it doesn't yet know about. Thinking back did anyone see a flop at the National this year? Did anyone see anything that wasn't finally well worth doing? No doubt 2004 will bring the stupid backlash, so let's remember that 2003 was a year of intensely exciting work at the National, produced in a new atmosphere of creativity and originality, all under Hytner's coolly politicised gaze. It had to be him. Encore's award for the artistic director of 2003 goes to

As good was his work on Edmond where the picaresque wanderings of the protagonist threw him into a series of locations only minimally picked out by the set but sharply drawn by fluid and imaginative changes in light. His Girl Friday, like his Democracy (National: Cottesloe) later in the year, was hemmed in by a rather restrictrive set and the on-stage lanterns looked decorative rather than integrated. His contribution to Mourning Becomes Electra (National: Lyttelton, pictured), however, was something else again. A bleached and unremitting palette of colours beat down on this tragedy, and swept the characters to the denouement. And what a denouement; Eve Best as Lavinia, the last remaining member of the doomed Mannon family, having seen the destruction of her father, mother, and brother, retreats into the family mansion. Bob Crowley's grand crumbling ruin swept across the stage, reforming as a long high corridor. As Best pushed open the door, the blood-red of the walls were battered out by a cruel deep blue that turned the passion to ice; as Best sinks to the ground, by now virtually a silhouette, Henderson has made the house into a tomb and it's his lighting, as much as Crowley's or Best's work, that shows us the full horror of the death that may be endured by the living.

The world beyond the house was as thrillingly realised as the world within, and the tones and hues that graduated throughout the design were hauntingly precise and aching in their emotional richness. This was rare work.

This is why we have chosen Hugh Vanstone as Encore's lighting designer of the year. Partly this is for his work on his fine work on The Pillowman with high beams interrogating the hapless writer, grimly enhancing the gun metal tones of the prison walls, alongside the witty cutaways into the storybook world; judicious unreality underscoring the unsettled world of the imagination. But mainly it is for The Lady from the Sea (pictured) that we offer this award. Opening the new, improved Almeida with this feast of colour, texture, of dappled light that suggested the waters sparkling around the characters even before myth takes hold of their hearts. Theatre light has that ability sometimes to make you forget where you are, to allow that dreamstate to take over, and here we forgot the vulgarity of this wealthy powerful audience, because here were theatrical pictures, rich in mood, simple, beautiful, magnificent.

There were spectacular designs that delighted this year; Giles Cadle and Michael Curry incarnated the world of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy and the creatures that inhabit it with restraint and power. Bob Crowley’s fading mansion for Mourning Becomes Electra’s transformed into the oak-panelled labyrinth within (and even became a ship, though with a kind of dramatic power and purpose that Tonight’s the Night can only dream at).

But it was a year where the most telling designs used minimalism, abstraction, clarity. It was rumoured that the extravagance of His Dark Materials was bought at the expense of the rest of the year’s design budgets, but actually the National’s designers did their best work on more limited means: Alison Chitty placed Scenes from the Big Picture in a blue box (pictured); the furniture and prop stacked up at the rear of the space encouraged us to see the big picture that accumulated around these scenes. The Pillowman (Scott Pask), also in the Cottesloe, played most of the action in a chilling and dark dungeon, the high walls only occasionally windowing out to show us the cruelties of a writer’s imagination. The best two shows in the £10 season were Henry V (Tim Hatley) and Edmond (Michael Pavelka), both of which stripped the Olivier back to a kind of huge studio arena, giving both productions an epic clarity. Neither Peter J Davison’s maisonette-work for Democracy, nor Vicki Mortimer’s junk-shop Jumpers served their productions, the designs appearing too self-involved and insufficiently organised, respectively.

Christopher Oram had a good year; he gave us a powerful traverse staging of Power (National: Cottesloe) allowing the courtiers of the Sun King to strut on a pre-revolutionary catwalk. For A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Crucible, Sheffield, pictured), he placed the action on bare boards, lit by a vast unblinking midsummer moon, giving the language space to work its madness. And for the Donmar’s Caligula he gilded a brick wall which shimmered and glowered in the light, a surface shot through with colour like a petrol slick on a wet road. It caught the surfaces of power, the brilliance and horror of rational tyranny, the emperor’s mixture of dazzling insight and flashing anger. The rest of the stage was left empty, apart from an elemental moment where a mirror is lifted from a pool to prompt further bottomless reflection on the grounds and ends of being and doing. It was a beautiful design, clear, magnificent and it stamped the production with cruelly dazzling authority. This was Encore’s design of the year.

It was certainly better than Tariq Ali's risible piece of political farce, The Illustrious Corpse (Leicester Haymarket), puffed up in the New Statesman as the inheritance of Piscator, Brecht, and Dario Fo. In your pinched dreams, sunshine. David Hare's docu-drama The Permanent Way (Out of Joint) was better, if aimed at a soft target, but at least suggested a sense of theatre as a medium in which people understand truths together. Hare inspired Neil LaBute's very unsatisfying The Mercy Seat (Almeida), as vacuous a piece of handwringing as we saw on the stage this year. The National misfired with two plays that seemed to be attempting an analysis of our current politics: Nick Dear's beautifully-written Power was a hypnotic and hilarious study of the court of the Sun King, but we waited on the edge of our seats for the links to current power politics really to have bite, but the bite never came. The same was true of Michael Frayn's Democracy (pictured), which revisited some of the dramatic devices of his glorious Copenhagen, but this time remained sunk in the research. Encore was divided on the merits of the play? Was this love letter to Willy Brandt codedly about Tony Blair? Was it about betrayal? The politics of image? The love between enemies? Or was it just a love letter to Willy Brandt? Or, worse, a love letter to Michael Frayn's bibliography of Willy Brandt?

This was a massive play, jetting across the world, interweaving a large number of individually fascinating stories in a rich whole. It was about a search for parenthood, the voraciousness of love, the connections we form across the world, the sublime banality of Hollywood, our need to beat away the natural world, and the eternal search for home. Building on the fragmentary-but-unified style of the same author's earlier The Cosmonaut's Last Message..., but this time narrated by 'David Greig', a quasi-authorial, omnimpotent figure, splintered throughout the play, dying and reappearing, with the world spinning around him. There was a wealth of humour in the play - two illegal immigrants solemnly singing "Band on the Run" at the improvised funeral of their adopted son, a charming joker in a psychiatric hospital, a wonderful pastiche of a disaster movie; but there was also passion in a pilot's savage denunciation of a vacuous rebranding exercise and in a woman's exquisite evocation of love: "I feel like I've suddenly fallen into the arms of an old, old city. Rome. He's Rome and I'm a Roman." It's a magnificent speech, reminiscent of Sarah Kane's ambivalent passion, but with Greig's unique stamp. The play was deprecated by some critics - we can only hope that, one day, in some late hour of the night, John Peter will realise his unsuitedness to the modern world, let alone the contemporary theatre, and fax an irretrievable resignation letter to the Sunday Times - but that's inevitable given the state of our critics. It was a big production, no doubt an expensive production, but it would have transferred beautifully to the Royal Court, the National, the Lyric, Hammersmith maybe. Yes it would have been a risk, but if safety is Fallout, let's take risks. For its vision, its beauty, its breathtaking evocation of our worldwide commitments and concerns, the Encore award for Best New Play 2003 goes to:

John Osborne's A Hotel in Amsterdam was handsomely revived at the Donmar, under Robin Lefevre's direction and with a searing central performance by Tom Hollander. Intriguingly, no one who watched the play can have wondered at the lack of any revivals since 1968: the play is poorly carpentered in places - the ending tried cheaply to bring the curtain down on a thrill of guilty horror - and, as is not unusual in Osborne, only the central character is painted with much psychological penetration. But it lived on that stage, it burned. And the saving grace of the ending is that it turned this nakedly autobiographical play against its author with cold fury. There were two Robert Holman revivals up at the Royal Exchange, Manchester, alongside a raft of readings; both shone. Rafts and Dreams was revealed as a rich, bold, visionary masterpiece, and Across Oka was displayed with love, gentle perception and abyssal emotional richness. It was good, too, to see Chris Hannan's Shining Souls (pictured), reupholstered and revisited in a melancholy, beautiful and vigorous production by V.amp at the Tron.

The National's His Girl Friday was comically underpowered, too, Alex Jennings seeming a little stiff for the play's moral gymnastics. The Traverse's commemorative revival of John Byrne's Slab Boys trilogy certainly reminded us of the play's greatness, but it was a rather wintry experience. Simon Russell Beale shone as ever in Stoppard's Jumpers, but it was a visually fragmented production and this wildly centrifugal play needed something more contained to marshal its verbal energies.