:: Encore Theatre Magazine ::

:: British Theatre: Polemics & Positions ::| [::..navigation..::] |

|---|

| :: Encore Front Page |

| :: Encore Heroes |

| :: Encore Futures |

| :: Encore Snapshots |

| :: Encore Polemics |

| :: Encore Resources |

| :: Encore Criticwatch |

| :: Encore Commentary |

| :: Encore on Encore |

| :: Encore Awards 2003 |

:: Friday, June 06, 2003 ::Encore Theatre Magazine

::Encore Revivals::The Evil Doers Chris Hannan [>]

The Blue Ball Paul Godfrey [>]

Epsom Downs Howard Brenton [>]

Their Very Own and Golden City Arnold Wesker [>]

Encore Revivals # 1:

The Evil Doers by Chris Hannan

Bush Theatre, 31 August 1990

“Glasgow. That’s the important thing. I’ve got a passion for this city! I’m perfectly open about that.”

The Evil Doers takes us through a day in Glasgow as an aspirational taxi driver, Sammy Doak (aka. ‘Danny Glasgow’), tries to interest tourists in his personalized tours round the city, while avoiding a loanshark, coping with his resentful daughter and alcoholic wife. The play is lyrical, hilarious, and city-wide.

No plot description can explain the beauty, warmth and poetic energy of Chris Hannan’s The Evil Doers, and surely nothing can explain or excuse its lack of professional revival since the premiere thirteen years ago. As in most of Hannan’s plays, the focus is on ordinary people, ordinary relationships, yet the writing always finds lyricism and emotional wildness in these characters and their lives. Here we find a chicken factory worker who reinvents himself as the personification of the new Glasgow, a girl whose passion for heavy metal bands with entire backlists and minutely visualized album covers, and a woman who declares ‘I only have sex in emergencies’.

The play premiered right in the middle of Glasgow’s year as European City of Culture. This - along with Mayfest and The Mahabharata at the revamped Tramway - was one of the cultural landmarks that fostered the revival of Scottish nationalism that would celebrate a successful devolution referendum at the other end of the decade; this most devolved of modern plays was part of that cultural revival. It inspired work by the next generation of Scottish playwrights, like Harrower’s Kill the Old Torture Their Young, Greig’s Caledonia Dreaming, even Greenhorn’s Passing Places. Perhaps more than any other play of its year, it inaugurated the 1990s; it refused to explain itself, it dragged us out of our domestic interiors into the big empty spaces, it reminded us of the richness and intensity of our lives.

And it's wonderfully funny; but this is an affectionate laughter that comes from the heart, not just the lips. (Even his stage directions are exuberant.) More importantly, Hannan’s dialogue is faithful to the elisions and fumblings of ordinary speech, but also rich with imagery and aching with feeling. Certain sentences he sets in brackets suggesting perhaps that another thought is interrupting the flow, forcing itself into the speaker’s mouth - their thoughts are as scattered and chaotic as the city in which they live. Their words flow over each other as they rush to speak, defend themselves, confess. Look at this tremendous exchange. Tracky, a teenager, has been upbraiding her father, Sammy, for failing to stick up for her against her mother:Tracky. And there was the time we’re flying back from Malta.It’s the sort of scene a novelist would never write; only someone who truly understands the stage could write it.

Sammy. (where are we now?)

Tracky. I’m eight and we’re flying back from Malta.

Sammy. Time (back and forwards like Einstein) I can’t keep up

Tracky. back from Malta and she slaps me in the face for nothing, because I was excited or something

Sammy. Where’s this again?

Tracky. (oh don’t deny it) she slaps me in the face and about (so many minutes later) you and her are snogging … you and her are snogging … you and her are snogging ...Tracky wipes at her eyes with her arm.

You never even told her off. She slaps me. So I sit there nearly greetin and nobody says nothing for like ten minutes. Then you and her start talking, then – five minutes – you turn your back on me and – start.

These characters are eccentrics; not because they scrabble after novelty – no, they are as ordinary as stone – but because they are somehow at a distance from the centre of things, their lives scattered and diffuse. They are eccentric in a play whose centre is Glasgow itself.

Hannan has referred to it as a ‘city comedy’ and it is one of the first contemporary plays to put a whole city on stage. Glasgow does make its presence insistently felt throughout. The Evil Doers oscillates between civic pride and disgust, between the old Clyde-built Glasgow and the new outward-looking European city. You can see it in the love-hate relationship between Sammy and his alcoholic wife: is Glasgow the spruced-up tourist-friendly taxi driver or the laddered Agnes who stumbles out of a drunken fight with a traffic warden to declare ‘I’m Glasgow’? The play doesn’t answer; it just overlays a number of possible Glasgows, one on another.

The Evil Doers will repay constant re-examination. In its generosity of attention, its expansiveness and richness, in the scale of its emotional intensities, it is as broad as a city itself. It is a modern masterpiece. Revive it!

:: Theatre Worker 4:23 PM [+] ::

...

Encore Revivals # 2::: Sunday, June 15, 2003 ::

The Blue Ball by Paul Godfrey

National Theatre: Cottesloe, 23 March 1995

“Being in space, I'd say it was

more incredible than you could imagine.”

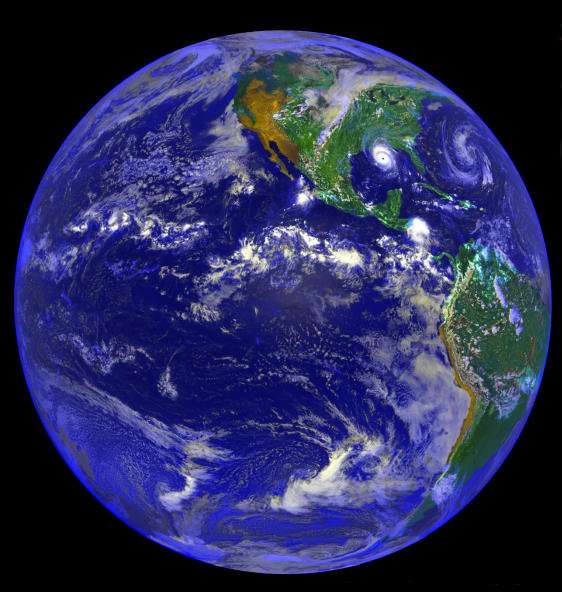

For two years in the early nineties, Paul Godfrey used a small travel grant from the National Theatre to visit the NASA space program in Florida and Star City near Moscow and interview the astronauts and cosmonauts. The result was the play The Blue Ball premiered in the Cottesloe in early Spring 1995.

The Blue Ball is a play full of space. In theme, it's a philosophical study of the meaning of space exploration and, in its form, it's an extraordinary exploration of the space of a theatre. Written in Godfrey's trademark terse, questioning, formal dialogue it's also a play which seems to contain the space for an intake of breath and a thought after every line, which is just as well because the play's ambition is so gloriously huge that it almost takes your breath away. Most 'ambitious' plays are chaotic, ramshackle, carnivalesque affairs. It is typical of Godfrey that The Blue Ball responds to the weight and scope of its themes with a modest, light, self-questioning style that at times almost seems not to be there at all. Take this exchange where Alex, chosen to be the first cosmonaut, returns from space and meets his wife.Anna: What was it like?Anna's 'What was it like?' is the question that functions as the play’s motor. When an experience has only been shared by a handful of people, yet it has captured the imagination of almost the entire world, how can we understand it? Only a few people know 'what it's like' and they don't seem to be able to convey that to us in any satisfactory way. The play has two central figures; Alex, a fictional character who is the mythical 'first man in space' (lightly based on Yuri Gagarin) and Paul, a playwright who is researching a play about space exploration (lightly based on Paul Godfrey).

He looks at her

And you're safe?

You're shaking.

Alex: I'm here.

I can stand

but I can feel the gravity pulling me down.

Anna: God.

Did you see God?

Alex: No, but I looked.

In one strand of writing we see encounters between Paul the playwright and people associated with the space program in Florida. In his first encounter, Paul meets Sylvie, an Astronaut:Paul: What's it like in space?Paul continues his journey in pursuit of the answer to 'what's it like' meeting, speaking to and recording the encounters with astronauts, physicists, their wives, and the space program technicians. As he progresses, the relentless inability of anyone to answer 'what's it like' becomes a challenge to Paul, the playwright - as if to say, 'How can you possibly represent space? It's beyond words.'

Sylvie: Being in space, I'd say it was

more incredible than you could imagine.

Paul: So what surprised you?

Sylvie: Everything.

Nothing could prepare you for that.

Paul: Can you be more specific?

Sylvie: Yes, the whole experience was a surprise.

Paul: In this play what must I show?

Sylvie: You've got to tell them about the wonder of it,

how overwhelming that is.Wound through these encounters are distilled, fictional scenes from a mythical space program (heavily reminiscent of the Russian one) in which a rocket scientist called Stone chooses Alex to be the first Cosmonaut. Alex goes in to space, returns, and then is faced with what it means to be the first man in space. His does not go into space again, his new role is as a symbol of the space program. He travels the world, he meets presidents and greets crowds. In time, Alex realises that his purpose in life is simply to answer the question 'what is it like?' over and over again. He ceases to speak and Stone's speechwriters write his words for him. His plangent last lines in the play seem to sum up his dilemma:

Alex: I wish I was an exceptional person.The action of the play remains firmly on earth. Since none of the characters are able to describe what space is 'like', Godfrey leaves us with only a gap where space should be - an inarticulacy, a silence, a look, a space defined purely by our inability to perceive it. In one typically wry moment Bob, an astronaut, describes what happens to the Challenger crew in the notorious Shuttle disaster. In doing so, he terrifies his wife, Nell and fascinates his friend, Roger, a physicist.

or had something unique to say.

Stone: What did you expect: transformation?

(aside) Why?

What is this question?

Why?

What does it mean?

Why?

Alarm bell rings.Bob: They were liquified.The Blue Ball is a play that demolishes metaphor. It takes you into a theatre and says - you must imagine. The play's sparse writing style and absence of stage direction seems to demand a production style with very limited décor: a blank canvas on which isolated figures are drawn. In setting himself the challenge of representing Space, Godfrey placed the bar very high. What can a writer do faced with the infinite unknown. With typical lightness he then leaps the bar. The Blue Ball - he represents Space with space.

The vibration and pressure

reduced them to jelly in their flight suits.

Roger: What a death,

and it could have been you.

Bob: That's what I thought.

Nell: I never heard this before.

Roger: Only bags of bones?

Bob: No bones left.

Judy: Do we need to know this?

We've just had dinner!

Bob: Could you put that in a play?

Paul: Anything's possible in a theatre.

The Blue Ball opened barely two months after Blasted, and it closed almost immediately, pulled from the schedules after a bombardment of uncomprehending reviews. The wave of writing which followed swept away an intriguing moment in British theatre when new writing was represented by Paul Godfrey, and Gregory Motton, and early Martin Crimp. It's so easy to forget these days that playwriting ever looked like this. The Blue Ball is a masterpiece; a diamond - hard, simple, full of light. Revive it!

:: Theatre Worker Friday, June 06, 2003 [+] ::

...

Encore Revivals # 3::: Monday, July 21, 2003 ::

Epsom Downs by Howard Brenton

Joint Stock: Roundhouse, 8 August 1977"I am the Derby Course. Don't be fooled by lush green curves in the countryside. I am dangerous. I am a bad-tempered bastard. I bite legs."

There is a moment that I fear happening whenever I see something on a epic scale, especially at the Olivier or the Barbican or the Lyttelton. It normally occurs when, for the forth or fifth time in the performance, some complicated piece of scenery is being rotated into place and a dozen actors in elaborate period costumes move offstage while a dozen different actors in different period costumes prepare to enter the new scene and this join is covered up by a dozen musicians performing specially commissioned period music. At such times I find myself thinking, was all this extravagance really necessary?

Joint Stock's 1977 play about the Derby avoids this problem of clutter and expense. Epsom Downs is a work founded on a sense of clarity that is beautiful in conception: a bare stage, the green Downs, the blue sky, just nine actors, only props and costumes such as are strictly necessary. And from this austerity springs a fountain of exuberance, imagination and spirit. Look at the open-hearted simplicity, and vigorous invention of this sequence which opens Act Two:The parade ring. A HORSE is being led around by a STABLE LAD.

HORSE. I am a Derby outside chance.

They parade.

The mentality of a race horse can be compared to the mentality of a bird. Nervous, quick, shy and rather stupid.

The HORSE flashes his teeth at the spectators. The STABLE LAD restrains him.

STABLE LAD. Don't give me a bad time.

HORSE. Many a racehorse has a fixed idea. Chewing blankets. Kicking buckets over. Biting blacksmiths.

They parade.

My fixed idea is that I must have a goat tied up with me, in my box. And there, tied to a stick in the yard, when I come back from the gallops. I will kick the place down, if I don't have my goat.

They parade

Where is my goat?

They parade

I want my goat!Character upon character and idea upon idea spill onto the stage: drunks, evangelists, horses, potentates, toddlers, peddlers, lunatics ... also the familiar Brenton (right) figures of philosophical policemen and the wrecked socialist idealist. The heightened stylisation of character demanded by the doubling and kaleidescopic intention of the production creates characters that seem marvellously full and rounded within a few minutes of their first speaking. Everyone in the play seems to have an action, a dilemma, a unique and valid perspective on the Derby, England, and life.

A silver jubilee production that was sadly forgotten at the time of the golden jubilee. One can only hope that somebody remembers Epsom Downs in time for the diamond jubilee of 2012. By concentrating on the primacy of human encounters and the spoken word, it is a truly epic production: not in physical scale, this is an epic of imagination and soul.

This stallion has been put out to stud prematurely. Let him gallop under the public's gaze again. Revive it!

:: Theatre Worker Sunday, June 15, 2003 [+] ::

...

Encore Revivals # 4

Their Very Own and Golden City by Arnold Wesker

National Theatre of Belgium, Brussels, November 1965; Royal Court Theatre, 19 May 1966"Supposing you had the chance to build a city, a new one, all the money in the world, supposing that; this new city – what would it look like?"

Arnold Wesker is fond of a story by Doris Lessing in which a soon-to-be-married gemstone merchant places a raw diamond on a table and circles it for three days before deciding how best to cut it for his wife’s ring. For Wesker, the story is analogous to the writing process where the source material dictates how it must be shaped and handled by the storyteller. In Their Very Own and Golden City, Wesker is cutting a political diamond: it's an ambitious play about the attempt to verbalize and enact a new social vision, and the compromises that undermine that vision. It looks back despairingly on the piecemeal reforms of the Attlee government (no doubt quickened by Wesker’s bitter experiences with Centre 42) and it anticipates the state-of-the-nation playwriting of the following decade.

The play opens in the vastness of Durham cathedral in 1926. A group of youngsters wander in, sketchbooks at the ready, awed by their surroundings. Amongst them is an aspiring young architect called Andrew Cobham, Wesker’s Master Builder, who dreams of constructing new cities that will change and democratize the world. Cobham’s journey in the play is one of gradual disillusionment and frustrated ambition as he is forced to scale down his plans and settle for a debilitating 'patchwork' version of his golden city project. On the one hand, then, the play tackles the containment and neutralization of radical vision by the forces of conservatism; on the other, however, it gives a searing theatrical expression to the social possibilities of architectural space. Golden City mourns the absence of a 'grand design' in politics, and documents the struggle for a language that is untrammelled by jargon, homilies, maxims, what we might now call 'spin' (indeed, the chanting of 'New Labour' by the youngsters in one scene attains a contemporary irony that Wesker could not possibly have foreseen).The composition of the play mirrors its thematic preoccupation with new designs for living, its scenes flowing into one another, creating an epic structure held together by echoes that resound across the years of the play. The Cathedral remains a constant framing presence as we watch, through a series of flashes-forward that take us from 1926 to the mid-eighties, attempts by Cobham and his friends to win support for their golden city project.

This dual-time structure underlay Wesker’s aspiration to have two groups of actors performing the play: one group onstage throughout, performing the roles of the excitable youngsters in the cathedral in 1926; the other group playing out the phases of their adult lives. This counterpoints the white-hot idealism of the youths with the increasingly embittered experience of the adults. The Royal Court damned the play from the start by using only one set of actors, since, without the double cast, the echoes and overlaps in the dialogue between present and future are theatrically unrealisable. Look at this short section from the final scene, in which the onstage presence of the older, thwarted Andrew Cobham is played against the bubbling, visionary idealism of his younger self. The flash-forward becomes the present, the Cathedral now becomes flashback, a memory on the point of extinction.YOUNG ANDY and YOUNG JESSIE rush into the open space and from different directions. They look at each other, shrug, and rush off again in new directions. Within seconds, STONEY rushes in from another direction, and off again. After a few seconds, ANDY slowly returns.Now read it again, bearing in mind Wesker's instruction that Young Andy's physical presence is provided by the young actor but the lines are spoken by the older man. The effect is to intensify the debate between idealism and practicality, and to fleetingly affirm the permanent necessity of hope.

YOUNG ANDY. I am as big as it. They build cathedrals for one man. It’s just big enough.

Closes eyes.

Show me love and I’ll hate no one. Give me wings and I’ll build you a city. Teach me to fly and I’ll do beautiful deeds. Hey God! Do you hear that? Beautiful deeds.

JESSIE AND STONEY rush in.

YOUNG JESSIE. They’ve locked us in.

YOUNG STONEY. Whose idea was it to explore the vaults? I knew we’d stayed there too long.

YOUNG JESSIE. They’ve locked us in.

YOUNG ANDY. I can’t believe there’s not one door open in this place.

YOUNG JESSIE. You and your stories about golden cities – they’ve locked us in.

YOUNG ANDY. I know there’s a door open, I tell you.

Wesker notes in his preface to the revised edition of the play that "it's too ambitious, the theme belongs to the cinema, it stretches across more time and action than the theatre should properly handle". Sure, it’s a sprawling and difficult work. It's shot through with resentment of Wilsonian bombast and patchwork politicking. Its focus on an individual hero with his own unique vision may be an eyebrow-raising premise for a socialist playwright. But this is no museum piece. Its concerns remain pressing: it’s an affirmation of political idealism, it's an excavation of political compromise. And it’s a play about cities as spaces of utopia and light. Their Very Own and Golden City is wrought with sweeping and brazen theatricality, through which an audience is compelled to visualise its own golden city. It cries out for an imaginative, large-scale and ambitious staging. Revive it!

:: Theatre Worker Monday, July 21, 2003 [+] ::

...