:: Encore Theatre Magazine ::

:: British Theatre: Polemics & Positions ::| [::..navigation..::] |

|---|

| :: Encore Revivals |

| :: Encore Heroes |

| :: Encore Futures |

| :: Encore Snapshots |

| :: Encore Polemics |

| :: Encore Resources |

| :: Encore Criticwatch |

| :: Encore Commentary |

| :: Encore on Encore |

| :: Encore Awards 2003 |

| [::..site feeds..::] |

| :: Atom |

| :: RSS |

Encore Theatre Magazine

::Front Page::

:: Saturday, July 22, 2006 ::

The Play's Not The Thing

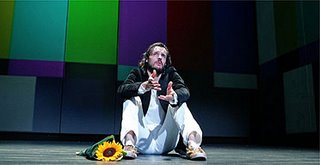

No one should be pleased to hear that The Play's the Thing winner, On the Third Day by Kate Betts (pictured), has posted closing notices. If anything, it demonstrates the case that Sonia Friedman seemed, occasionally, to have thought she was making: that new plays have no place in the West End. Friedman's attempt to turn this failure into a success by arguing that 51% houses for seven weeks at the New Ambassadors would be a huge success at the Court. Actually, according to those figures, the number of people who saw it was 12,681, which would comfortably fit into the Royal Court downstairs running the same number of performances for a month.

Which would be a success, but had happened several times without the benefit of a reality TV show behind it. The fact is that even with that strange, funny, engaging, enraging TV series, not enough people were persuaded to go to see Kate Betts's play.

Maybe the original question is misconceived. Why aren't new plays opening in the West End? Because it's not the best place for them. The last time new plays opened in large numbers in the West End was probably fifty years ago, before the idea of 'new writing' theatres existed, and certainly were not subsidised by the public money. Then a new play would have to appeal to thousands. This produced some wonderfully interesting work - Rattigan, Coward, Ackland, Priestley and many others, produced durable work that had depth as well as popular appeal - but undoubtedly closed off avenues of creativity in those writers. Priestley, for example, rarely seems wholly comfortable as he tries to import narrative experimentalism into his drawing room dramas. Ackland's moral disgust ran foul of the conservative critics, and pleasing the audience gave way to a longing to be liked that finally blunted Rattigan's and Coward's gifts.

And now we have an enviable network of theatres who either exclusively or regularly produce new plays. And these are almost exclusively publically funded. Perhaps it is true that this breeds the opposite quality - a contempt for the audience - immunised against their dislike, though this would be a dubious claim - what playwright of merit despises the audience? All the immediate names that come to mind - Osborne, Kane - are actually classicists of form, who draw in the audience with humour and structural grace, even as they outrage against the proprieties of form. There are writers like Martin Crimp whose coolness can be icy, but this is an iciness that we have come to enjoy (perhaps supremely) and it is a profound pleasure that the commercial theatre would not have discovered.What lurks behind this quest for the West End play is a desire for a new generation that will follow Ayckbourn and Stoppard as names that can themselves sell a play, people whose acidity is sweetened by humour, who unfailingly know what a public can take and give them that and a zingy bit more.

But this won't happen. At least it won't happen by trying to get playwrights to write differently. The West End audience is like the membership of the conservative party; ageing, and therefore, sadly, also dying. The current production styles in the West End, the acting, the design, the style of the programmes, the decor, the bars, the timings, are all designed for that audience. (Of course, they are the ones who come, after all.) But these are rather unattractive to most people under the age of fifty. There is a different sensibility at work, which finds character clumsy, theatrical stories laborious, and the ponderous one-eye-on-the-audience cheat-it-out-front acting, Wendy-house sets, lame jokes, cramped bars, waistcoated ice-cream sellers, smelly auditoria, and inconvenient curtain times (when do you eat??) entirely offputting.

Trying to encourage new commercially-minded playwrights is tinkering, a classic instance of rearranging the deckchairs. The buildings need a complete overhaul, not the kitschy makeovers that some of them (see picture) have had. Some of them will need to acquire expensive surrounding buildings to tunnel into. Others will need to close. The theatre owners can barely afford to keep most of these buildings open, which leaves only the option that Encore has canvassed before. Nationalise the West End.

Photos by Tristram Kenton and Christopher Holt.

...

Comments:

It seems I can. What an elegant and provoking piece. I think it goes too far in attempting to draw general conclusions from the unusual specific of "The Play's the Thing", which I thought did at least make interesting television. That it didn't make good theatre is no surprise. If I may briefly drag you down the lanes of memory, in 1956 the Observer held a new play competition, of which the first prize was to be a production at the Royal Court. Very like "The Play's the Thing", this production, for all the vast prestige of The Observer in those days, had little success and played (I bet) to a lot fewer people than saw "On the Third Day" did. Competitions never produce good plays. I don't know why, it's just one of those things, The Royal Exchange's annual Mobile competition is another example. (Does it still exist? Is it still called that? Too late at night to Google.)

The questions you ask are so interesting that your answer - nasty theatres - is doubly disappointing. Would that it were true, but it just isn't. There is literally no West End Theatre, however awful in terms of comfort and appeal, that I haven't seen packed out with a mixed and unaccustomed audience at some time or another. It depends on the show. What building could be more dismal than the Lyceum, where "The Lion King" is full every night? What could be more tacky and naff than that theatre in Hammersmith ... Labatt's Apollo?? - that sells out for rock concerts. Kids go to concerts where the mud is knee-deep and where they end up hitching lifts on motorways at dawn. Comfort, appeal and a sympathetic environment are nothing to do with it. I say this with some regret, since it makes all our lives so much more difficult, but it really is only the show that counts. Best wishes to you all anyway.

The questions you ask are so interesting that your answer - nasty theatres - is doubly disappointing. Would that it were true, but it just isn't. There is literally no West End Theatre, however awful in terms of comfort and appeal, that I haven't seen packed out with a mixed and unaccustomed audience at some time or another. It depends on the show. What building could be more dismal than the Lyceum, where "The Lion King" is full every night? What could be more tacky and naff than that theatre in Hammersmith ... Labatt's Apollo?? - that sells out for rock concerts. Kids go to concerts where the mud is knee-deep and where they end up hitching lifts on motorways at dawn. Comfort, appeal and a sympathetic environment are nothing to do with it. I say this with some regret, since it makes all our lives so much more difficult, but it really is only the show that counts. Best wishes to you all anyway.

Having (like all retaliatory bloggers) re-read what I was blasting about and realising that I'd missed half of it out. You vastly under-rate the delightful effect of creaky plotting and conventional forms. What could be more joyously old-fashioned than "See How They Run", which went like a bomb the night I saw it, and deservedly so. (As you, or perhaps a more liberally-minded post-modernist, concede in a different piece).

from a different anonymous - three separate points, in response to anon and encore...

i'm not sure that competitions throw up a worse bunch of plays than the deeply flawed literary management system. i remember the third placed play in the final mobil competition was actually a rather good piece by phyllis nagy. let's see what happens with the successor to the mobil competition (defunct for at least ten years, i think), the (wonderfully, anonymous) bruntwood.

i think it's perhaps over-stating the case to say this generation finds character clumsy and theatrical stories laborious. there are ways of writing character that might be clumsy, and ways of telling stories that might feel laborious. but one thing that isn't sufficiently recognized is that there are as many ways of writing characters as there are of sketching a human figure, as many ways of telling a story on stage as there are of painting water. new writing theatres sometimes seem to give the impression that there's only one way, and this is false (and quite a dangerous idea, in fact, because it can end in some powerful individuals propagating aesthetic preferences under the guise of matters of good or bad technique)

it's good that we have the new writing theatres because they give a space for work that would never have found a home in the old purely commercial world. it's bad, because there's now a kind of career path for writers that means that one has to be able to train oneself to write a little studio play before being permitted to put work on bigger stages. and for some people, writing that kind of play isn't easy (whereas bolder work might be). the result can be that the new stoppards, and ayckbourns, and cowards (and even pinters and frayns) see their work excluded from the theatre entirely, because they've never managed to write the intimate, naturalistic, not overtly theatrical piece that's going to get them their first production in the theatre upstairs..

i'm not sure that competitions throw up a worse bunch of plays than the deeply flawed literary management system. i remember the third placed play in the final mobil competition was actually a rather good piece by phyllis nagy. let's see what happens with the successor to the mobil competition (defunct for at least ten years, i think), the (wonderfully, anonymous) bruntwood.

i think it's perhaps over-stating the case to say this generation finds character clumsy and theatrical stories laborious. there are ways of writing character that might be clumsy, and ways of telling stories that might feel laborious. but one thing that isn't sufficiently recognized is that there are as many ways of writing characters as there are of sketching a human figure, as many ways of telling a story on stage as there are of painting water. new writing theatres sometimes seem to give the impression that there's only one way, and this is false (and quite a dangerous idea, in fact, because it can end in some powerful individuals propagating aesthetic preferences under the guise of matters of good or bad technique)

it's good that we have the new writing theatres because they give a space for work that would never have found a home in the old purely commercial world. it's bad, because there's now a kind of career path for writers that means that one has to be able to train oneself to write a little studio play before being permitted to put work on bigger stages. and for some people, writing that kind of play isn't easy (whereas bolder work might be). the result can be that the new stoppards, and ayckbourns, and cowards (and even pinters and frayns) see their work excluded from the theatre entirely, because they've never managed to write the intimate, naturalistic, not overtly theatrical piece that's going to get them their first production in the theatre upstairs..

Very interesting responses. I agree that we shouldn't overstate the shabbiness of the buildings - but (a) we didn't, really, it was listed alongside a lot of other aspects of the West End experience that is offputting (even to regular theatregoers like us), (b) yes of course all West End theatres have sometimes had one-off successes, but the fact that they can't build on these to get a regular youngish audience may be because the one-off experience is marred by the various discomforts they have experienced, and (c) it's horses for courses; yes, young people (and some older people too) are happy to put up with all kinds of indignities to see bands (being bruised to a pulp in the mosh-pit, queueing for hours, seeing a band in rain and mud, sleeping in a tent and shitting in an overflowing portaloo, etc etc.) this is part of the mystique of rock and pop - it's not part of theatre (unless we see the Glasto theatre tent as the future of theatre which we at Encore really don't). It's horses for courses. It would be great to imagine a piece of theatre for which hundreds of 19-year-olds would willingly hitch home, but it seems too unlikely. But: you're right, it's not about swanky bars and groovy seating. Much more important is the crappy amateurishness of what's on stage.

As to the second response about the plotting and playmaking, we weren't trying to say that all character and all narrative are out of step. And in any case, the theatre shouldn't be slavish in its quest for young audiences - often you end up trashing the very thing you are trying to defend (cf. Barker's A Hard Heart for a beautiful dramatisation of this principle). But doesn't a certain kind of ennui strike you when you see what David Eldridge once called 'that clunky what-around-the-corner plotting'? I do genuinely think a lightness of plotting and character feels more engaged with the present, somehow more current. These things are notoriously hard to judge though.

Pinter. Yes, this is a great counter-example. The writer who was a hit in the West End before he got properly taken up by the subsidized sector. (Though several of his pre-Caretaker plays were supported by public money: The Room at a university, some BBC radio plays.) But would Pinter get discovered by the West End now? And would he have to be discovered by the West End now?

The Mobil competition is indeed long gone. If my memory serves me well, the latest incarnation is now exclusively for young writers. Sign of the times. And of desperation?

Post a Comment

As to the second response about the plotting and playmaking, we weren't trying to say that all character and all narrative are out of step. And in any case, the theatre shouldn't be slavish in its quest for young audiences - often you end up trashing the very thing you are trying to defend (cf. Barker's A Hard Heart for a beautiful dramatisation of this principle). But doesn't a certain kind of ennui strike you when you see what David Eldridge once called 'that clunky what-around-the-corner plotting'? I do genuinely think a lightness of plotting and character feels more engaged with the present, somehow more current. These things are notoriously hard to judge though.

Pinter. Yes, this is a great counter-example. The writer who was a hit in the West End before he got properly taken up by the subsidized sector. (Though several of his pre-Caretaker plays were supported by public money: The Room at a university, some BBC radio plays.) But would Pinter get discovered by the West End now? And would he have to be discovered by the West End now?

The Mobil competition is indeed long gone. If my memory serves me well, the latest incarnation is now exclusively for young writers. Sign of the times. And of desperation?